The Western Australian Council of Social Service Inc. (WACOSS) welcomes the opportunity to contribute a submission to this inquiry.

WACOSS regularly convenes the Children’s Policy Advisory Council (CPAC), which brings together member organisations to ensure a cohesive whole of sector response is developed around children’s policy in Western Australia. Input and insights from attendees at the regular consultative forums are used to directly shape WACOSS policy agenda, engagement with key decision makers, and advocacy to improve outcomes for children, young people and families in Western Australia.

Recommendations

- Commission an independent report on child development services in WA that specifically addresses the issues of:

- Current and future population need & service planning

- Service models, costs and outcomes in comparison to other jurisdictions

- Wait times and waiting lists, and what alternative support should be offered in the interim

- Access and outcomes for at risk population groups (e.g. low SES areas, Aboriginal, CALD, regional & remote) relative to population need.

- Develop outreach strategies and priority referral pathways for families in crisis or recovering from trauma, including family violence, child protection and homeless services.

- Review screening and referral pathways for early developmental delay, including child health nurses, child and parent centres, and early education and care services. Include simplified referral pathways to speech pathologists and occupational therapists for confirmation and

- Develop principles and practices for active outreach and effective communication with parents of children experiencing developmental delay to enable them to be part of a sustainable and effective solution.

- Review rates of intellectual disability and neurodiverse diagnoses within WA schools by location in comparison to school services & resources and referral pathways.

- Develop programs for young people whose needs were not identified earlier and no longer fit the priority age range for child development services.

- Increase access to maternal, child and youth mental health

- Develop policies and incentives to retain existing skilled early education and care staff, including greater job certainty and improved employment conditions.

- Prioritise the development and provision of childcare services in regional areas as a key support for regional development outcomes.

- Address barriers to childcare access for parents seeking work, particularly single

- Progress universal access to quality education and care as an economic development

The importance of early child development

The early years are the most critical time in our life. It is when our bodies and brains are developing at their fastest rate and laying the foundations for lifelong development and wellbeing.

Early investment in healthy development is the best way we can ensure our children thrive. Happy, healthy, safe and connected kids grow into well-balanced and resilient young people and into productive and caring adults with fewer health and mental health problems, barriers to social and economic participation. Early development is critical to lifelong capability and potential, and the evidence is very clear that early disadvantages can accumulate to have an impact through the life- course. The sooner we are able to identify and address developmental concerns the better the developmental outcomes.1

We contributed to the development of the report The Early Years: Investing in Our Future released by Bankwest Curtin Economic Centre in August 2020 (attached) which provides a demographic profile of the number and share of children in WA from pregnancy through infancy and toddlerhood to preschool. It covers health and mental health outcomes for mothers and children as well as language development and access to early education and care to develop and present an Early Learning Disadvantage Index.

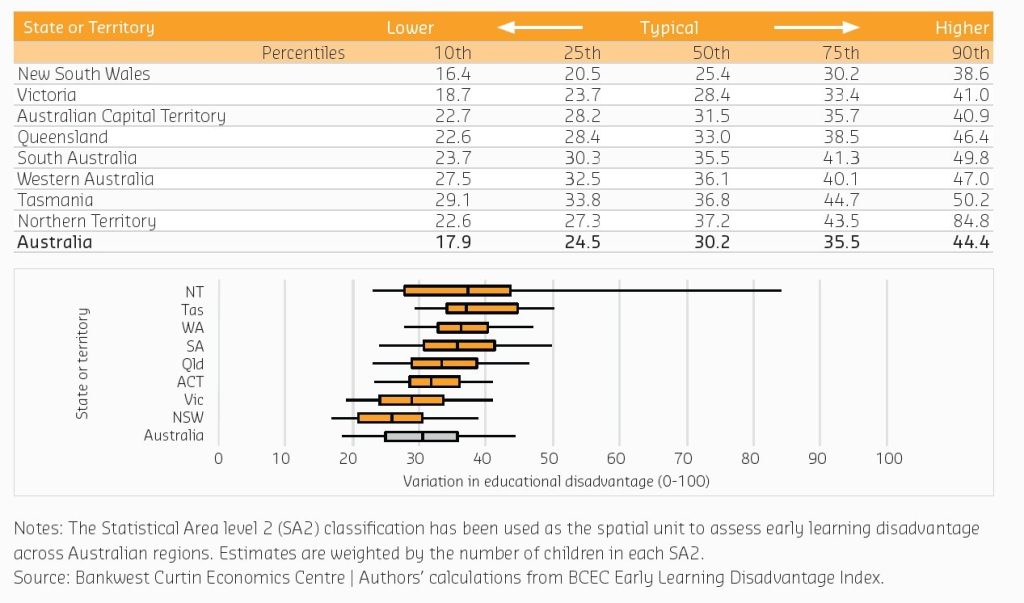

Table 1 – Within State variation in BCEC Early Learning Disadvantage index

The report highlights the incidence and depth of child poverty within WA, revealing how poverty increases the risk of early developmental delay and creates barriers to access to early learning opportunities and early development services.

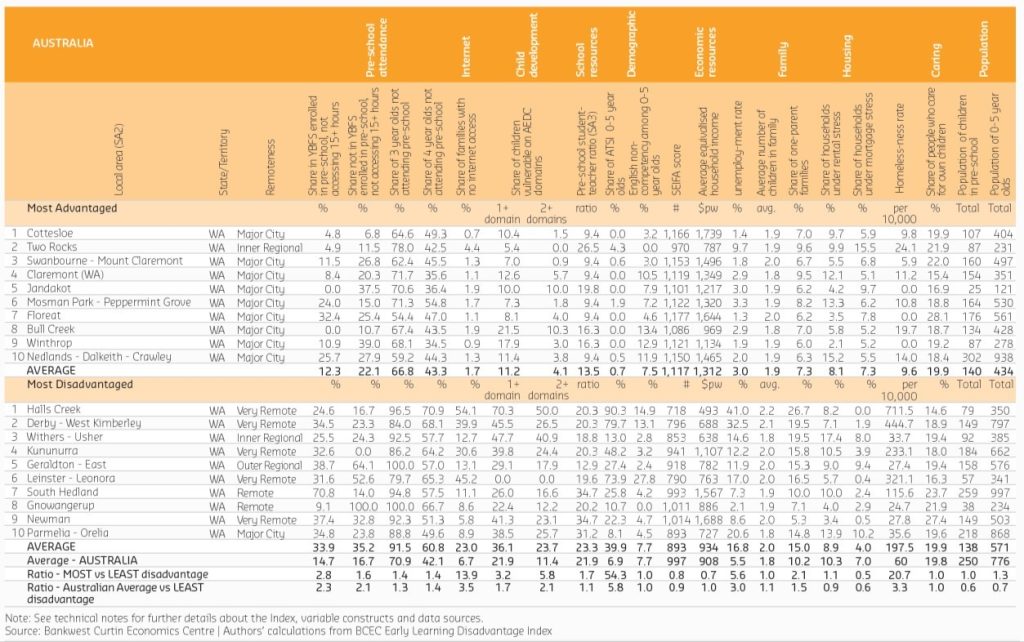

Children living in the most disadvantaged areas in Western Australia are less likely to be accessing the benchmark of 15 hours of preschool each week in their year before school, than the national average. Around one-third of enrolled children are not attending preschool for 15 or more hours each week, compared to only 12.3 per cent of children in the most advantaged areas. Children in the most disadvantaged areas in WA also have high rates of developmental vulnerabilities, with 1 in 3 children assessed as developmentally vulnerable on one or more domain and 1 in 5 developmentally vulnerable on two or more domains.

The report found that 16% of toddlers in WA had socio-emotional competence problems, 24% had behavioural problems and 20% had delayed language development. These numbers increased to 44%, 44% and 40% respectively if the infant was growing up in an environment with limited parental affection or engagement. Approximately 30% of toddlers from households living in severe poverty were estimated to have delays in language development, which is twice the rate of those not living in poverty. 50% of children living in the most disadvantaged areas in Western Australia are developmentally vulnerable on two or more domains, compared with national average of 11%.

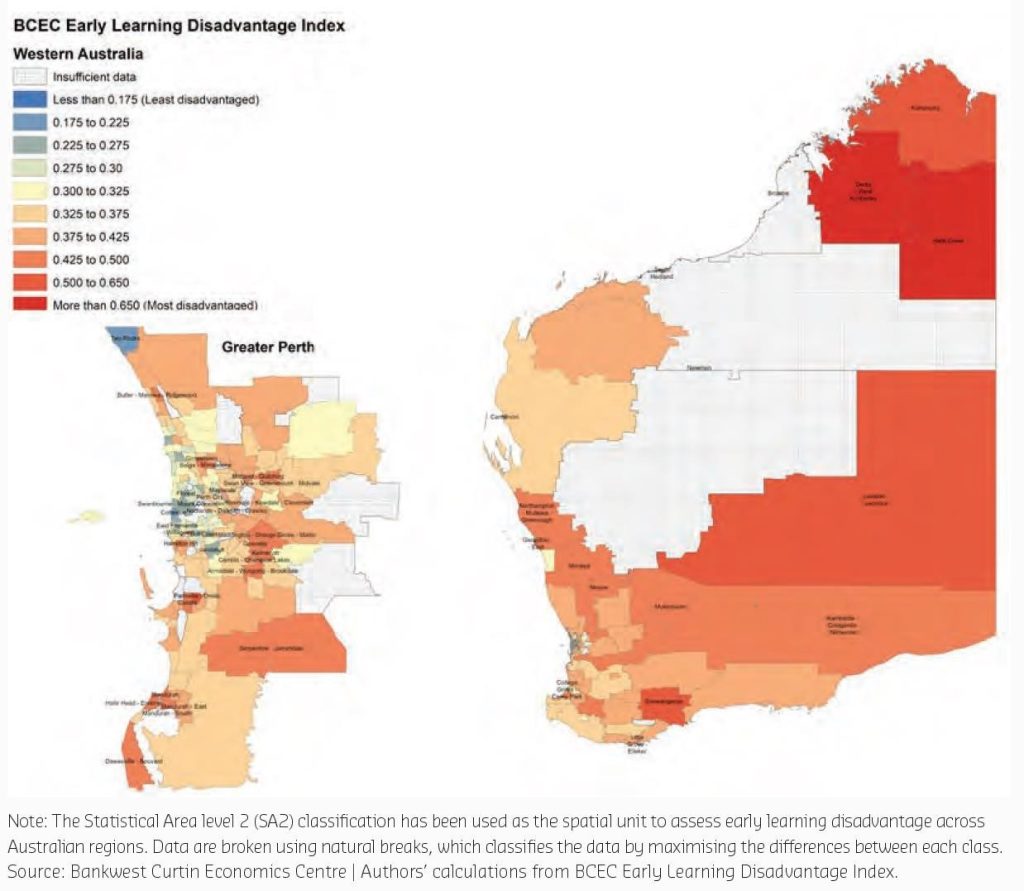

Figure 1 – Early learning disadvantage in WA

Table 2 – Most and least disadvantaged areas in early learning in WA

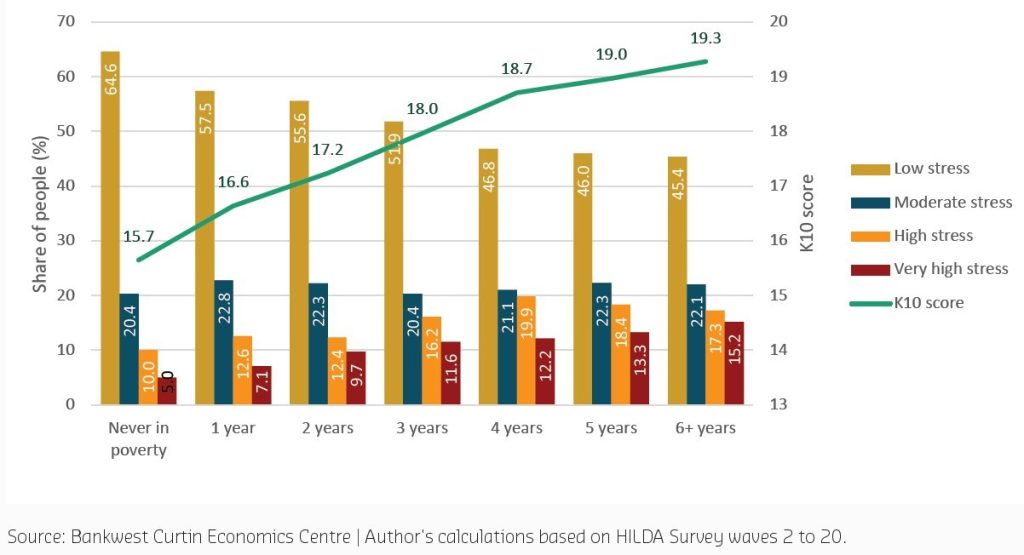

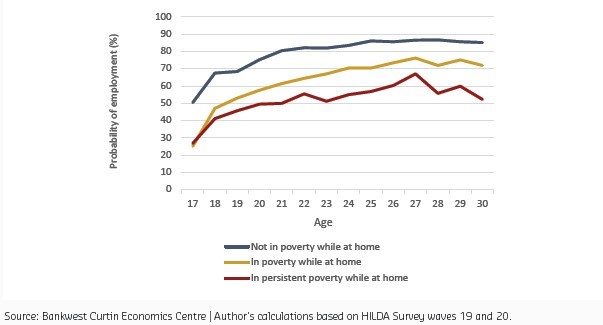

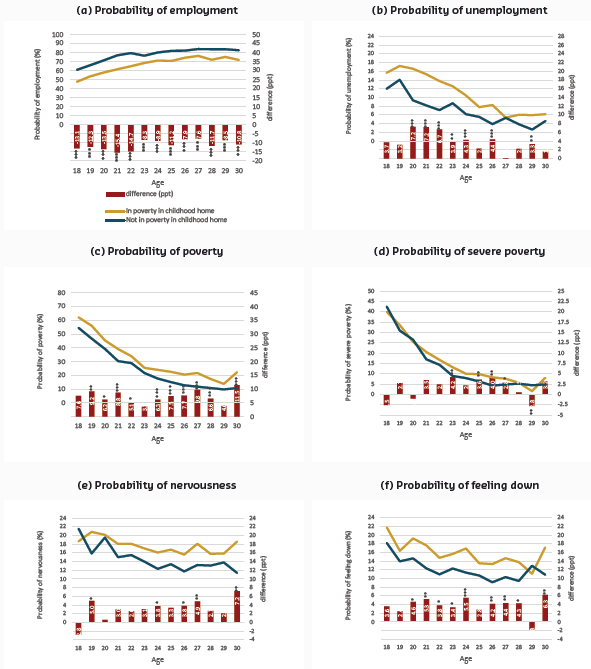

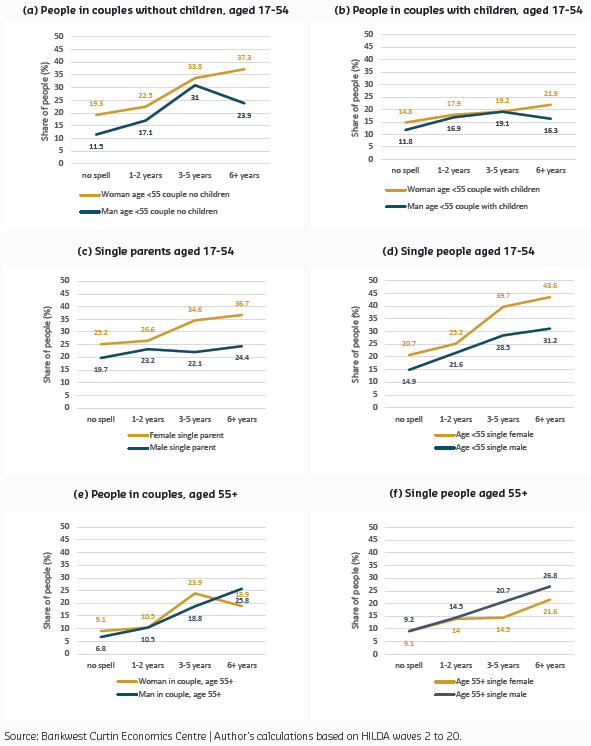

The 2022 BCEC report Behind the Lines: Poverty and disadvantage in Australia adds to this analysis by showing the impacts that growing up in poverty has on adult outcomes. The research shows a strong association between persistent poverty and psychological distress (Figures 2 & 4) and that childhood experience of poverty leads to much poorer employment and financial security outcomes in later life (Figures 3 & 5).

In 2020 in Australia 750,000 children were living in families below the income poverty line, with over 190,000 experiencing severe poverty. People who experience childhood poverty are up to 8 percentage points more likely to remain in poverty in adult life. The chances of securing future employment after a poverty in childhood are up to 11 percentage points lower compared to those who did not come from a poor childhood background, and they are significantly more likely to suffer from nervousness or feel unhappy with their lives for up to 10 years after leaving home.

Figure 2 – The relationship between persistent poverty and psychological distress

Figure 3 – Adult employment rates (age 17 to 30) vs persistent family poverty in childhood

Figure 4 – Impact of childhood poverty on adult outcomes after leaving the family home

Figure 5 – Number of years in poverty and prevalence of psychological distress by gender

Families living in poverty experience a wider range of vulnerabilities and experience much higher rates of social isolation.

Research by Telethon Kids Institute also highlights the effects of poverty. Monks (2017) report The impact of poverty on child development2 finds that poverty in the first five years of life is particularly harmful to children’s development, highlighting children in single parent families are three times more likely to be at risk. It aligns with other TKI analysis (eg Zubrick 2018, attached) that concludes that it is not so much poverty but the impacts that depravation has on early relationships and experiences on young children’s health and development. ‘Working poor’ households for example, where there is both limited access to developmental opportunities and resources, and where parents are time poor and stressed are of particular concern. This analysis suggests that intervening during the early years can break the cycle of disadvantage, if we are able to assist parents to cope effectively with disadvantage to provide consistent and responsive care. Parents under stress are likely to try to shield their children from their negative emotions out of concern, however the risk is that they can then become emotionally unavailable and withdrawn, rather than finding positive ways to engage.

There are some important issues to note here. The relationship with the parent or parents (or primary carer or carers) is the most significant for the developing child. It is the one in which they are most emotionally and developmentally invested and in which they spend the majority of their time. Hence effective interventions to assist developmentally at-risk children also need to include and support the primary carer. It can be helpful to provide other opportunities to connect and socialise with other adults and other children, however the child’s ability to engage and benefit from these activities may be limited by these fundamentals.

The biology and neurobiology of development suggests that early experiences can get ‘under the skin’ in a way that shapes lifelong health. Growing up in chaotic, unpredictable environments where children experience toxic stress can limit early brain development and mean the child is constantly vigilant or easily triggering survival reactions. Children starting early education and socialisation who are less ready and able to engage can be increasingly left behind – early development is a cumulative process and early disadvantages can quickly accumulate. (Shanker)

Monks (2017) also highlights the interaction between socio-economic status and developmental mobility in AEDC data in relation to the capacity of children with poor school readiness to be able to catch up on educational outcomes over time, concluding “despite poor school readiness, children of med-high SES can catch up within the first few years of starting school, but children of low SES do not demonstrate this same level of developmental mobility, and continue on a poor educational trajectory.” Conversely, the data also shows that good school readiness helps children from a low SES background to do well at school, saying “…if a low-SES child starts school with a good level of school readiness (high scores on the AEDC) then this appears to act as a protective factor, and they continue to achieve at an average level of academic achievement throughout school.”

Efforts to develop more integrated early childhood services in WA

WA’s current approach to providing support to mothers and children in the early years of life is fragmented and inconsistent – meaning that whether or not those at risk are able to get timely access to advice and support depends on where they live and their capacity to navigate health and social services across multiple government and NFP agencies

Better Together: Supporting Perinatal and Infant Mental Health Services (BCEC 2019 attached) found that parents of infants seeking support struggled to engage with professional services to get meaningful and useful advice they could understand and act on, felt judged and disrespected, and were often frustrated by the lack of simple access and referral pathways.

Service system design needs to put the child and the parents at the centre, taking a wrap around and no-wrong-door approach to ensure that developmental needs and risks are identified early and dealt with effectively in a way that parents can understand and own.

WACOSS, the Mental Health Commission, the City of Cockburn and local child and family services undertook a project in 2012-13 to develop a model for integrating services to support the mental health of infants and young children. This led to the production of two reports Integrating services to support the mental health of infants and young children: Developing the concepts (WACOSS 2013, attached) followed by Applying the concepts (WACOSS 2014, attached).

Around this time, we also helped to establish the Connecting Communities for Kids project in the Cockburn and Kwinana local government areas through the Partnership Forum Early Years Working Group. The project has continued to have a significant impact on children and families in its’ local area by better connecting services and families through an integrated place-based model. However, we were unsuccessful in securing funding for ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the project, so were unable to progress the project’s original intent to pilot a model where the learnings could be shared in partnership to assist other local and regional areas with poor child development outcomes to adopt and adapt similar integrated place-based approaches.

There remains an opportunity to learn from and extend this model elsewhere, and to look more closely at the remaining barriers to family engagement and early child development in this local area, as seen in recent AEDC results for the Cockburn/ Kwinana region.

Addressing Terms of Reference

We commend the WA Parliament for establishing this inquiry.

Select Committee terms of reference:

- the role of child development services on a child’s overall development, health and wellbeing;

- the delivery of child development services in both metropolitan and regional Western Australia, including paediatric and allied health services;

- the role of specialist medical colleges, universities and other training bodies in establishing sufficient workforce pathways;

- opportunities to increase engagement in the primary care sector including improved collaboration across both government and non-government child development services including Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations; and

- other government child development service models and programs operating outside of Western Australia and the applicability of those programs to the State.

As the peak body for the community services sector in WA, our membership includes community- based child and family services and not-for-profit early education and care services, a well as those in areas such as child protection and out-of-home care, youth crisis service and the like. We have less direct insight into child development services in the paediatric health and allied health space, although many of our members interact with and refer to these services to coordinate the support of children in their care. We strongly support the role of Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisations in the delivery of services to Aboriginal children, families and communities, supported the development of the Noongar Family Safety and Wellbeing Council, and continue to work with the Aboriginal Health Council of WA to support the establishment of a state-wide Aboriginal community service peak body. We are currently leading work with the Department of Health to develop a partnership framework and increase collaboration between health services and social services to improve community-based prevention, early intervention and recovery as part of the Sustainable Health Review.

In relation to the terms of reference, we highlight the role of child development services (a) within the broader context of the critical role of the relationship with the parent(s) or primary carer(s) in early child development and wellbeing. We note the importance of the child’s early environment and experiences to healthy early development, including access to quality early education and care services. Universal access to quality education and care should be our starting point, with integration of early development screening for all children into these services, with targeted outreach and support to those families and communities most at risk. We need to have clear referral pathways alongside appropriate and effective parental communications and support.

Timely access to specialist child development services can play a critical role in addressing early development problems and developmental delay, hence issues of equity in access, affordability and waiting lists are of major concern. We want to see greater availability of these services and reduced wait times, particularly in those areas and regions where children are most at risk. These services should work in complement with universal health and education services, and the risk is that gaps in primary care can mean developmental risks are not identified early enough and developmental issues compound to make the task of specialist services more complex, the outcomes less promising, and the costs much greater.

We cannot offer much data or insight in relation to the availability of specialist child development services in metro and regional areas (b), other than reflecting the concerns raised by our members that services are hard to access and waiting lists are long, and that there few services and increasing access barriers for those in regional and remote areas. We have attached some analysis of access to early learning services, preschool enrolment and attendance and child health check data from the BCEC (2020) The Early Years report.

Child and Adolescent Health Service WA (CAHS 2022) data shows increasing demand for discipline referrals, which rose 8% in the last year and 24% over the last 3 years. Demand for autism assessment rose by 12% last year and by 82% in the last 5 years, increasing to 550 formal referrals in 2021-22. Allied service provision also increased by 9%.

WACOSS have little insight to offer specifically in relation to workforce pathways and training of professional staff for specialist development services (c). We draw the committee’s attention to our recent submissions on Delivering a Skilled Workforce for WA, and the Senate Inquiry on Work and Care in relation to the broader workforce attraction and retention crisis in the early education and care sector. There is strong evidence that poor pay and conditions for early childhood educators is limiting access to early education and care services, with many services forced to restrict enrolments, shut rooms or close premises due to a lack of staff, particularly in regional areas and on the urban fringe.

The early education and care workforce is projected to increase by over 10% nationally between 2020 and 2025, requiring an additional 154,000 workers nationally and around 16,000 in WA. Higher rates of workforce development will be needed if we are to increase the workforce participation rate of women within the WA labour market (now up to 64.5%, vs 74.8% for men) and to increase the proportion of women working fulltime (51.5%, vs 82.6% for men).3 Recent member survey data from the United Workers Union indicated that 46% of current workers are burnt out and considering leaving the sector within the next 1-2 years. 4

While the WA Government has announced a program to offer subsidised VET courses for early educators, more is needed to improve retention of existing staff and address the very high dropout rate of new graduates. Skilled staff are needed to provide on-the-job training, mentoring and supervision and to meet legislated standards.

For any enquiries about this submission please contact Chris Twomey, Lead Policy & Research, [email protected].

References

1 William Teager, Stacey Fox and Neil Stafford, (2019) How Australia can invest early and return more: A new look at the $15b cost and opportunity. Telethon Kids Institute. See also BCEC (2020) The Early Years (attached), CCYP WA (2019) Improving the Odds for WA’s vulnerable children and young people.

2 H Monks (2017) The impact of poverty on the developing child, Telethon Kids Institute.

3 WA Women’s Report Card 2022. BCEC & Department of Communities.

4 Exhausted, undervalued and leaving: The crisis in early education. United Workers Union, August 2022