The Western Australian Council of Social Service Inc. (WACOSS) welcomes the opportunity to contribute a submission to the Senate Select Committee on Work and Care.

Recommendations

Adequate, sustainable funding for the community service sector

- Indexation and resourcing of State and Federal contracts must be sufficient to ensure award obligations can be met

- Public authorities should contract with the not-for-profit community services sector in a manner that supports sustainable and effective service delivery and greater parity in pay and conditions for community services workers

On the job training

- Support greater links and partnerships between training providers and community service organisations,

- Recognise the importance of worker training in procurement policies

Aboriginal Community Service Sector Workforce Development

- Develop an Aboriginal workforce development strategy that provides incentives and support to increase Aboriginal employment in human services contracts

- Establish requirements in State and Federal Government contracts to train and employ people within the local community with a focus on Aboriginal workers.

Early Childhood Education and increasing workforce participation

- Encourage and support early childhood centres to provide on-site training and professional development and provide scholarship funding to up-skill experienced staff to provide supervision and mentoring.

- Develop policies and incentives to retain existing skilled early education and care staff, including greater job certainty and improved employment conditions.

- Prioritise the development and provision of childcare services in regional areas as a key support for regional development outcomes.

- Address barriers to childcare access for parents seeking work, particularly single mothers.

- Progress universal access to quality education and care as an economic development priority.

Labour market trends across care industry workforces

- Develop collaborative reform approaches to service delivery and funding models in aged care, disability and childcare services through COAG as a national priority.

- Prioritise secure work arrangements and continuity of care across human services.

- Pursue industry-level gender equity outcomes through Fair Work Australia.

- Develop productivity metrics that capture the true value of care service including, for example, the additional participation and productivity of family carers and the future productivity of healthy well-educated children as adults.

Housing

- Develop housing initiatives that ensure provision of accommodation for employees of Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) contracted and funded by the State or Federal Government to provide key services in regional locations

- Incorporate housing costs into service delivery contracts in high-cost regional locations to sustain the delivery of funded NGO services

Recognising the community sector’s value and contribution

Targeted transitional investment in job creation and training in areas of unmet and growing need, such as aged care, disability services, FDV services, ACCO services.

Introduction: Work and care in challenging times

Our submission draws on some of our recent work to contribute to the WA Government inquiry into Delivering a Skilled Workforce in Australia as well as our efforts to provide information to key stakeholders ahead on the National Jobs and Skills Summit. We note that WACOSS and the community sector in WA are also contributing to a report on Population and Skills in Western Australia by the Bankwest Curtin Economic Centre which is due for publication in mid-September and includes a specific focus on emerging workforce issues within the aged care and early childhood education and care sectors in WA (after submissions close). We recommend the committee consider this report once it is published if that is at all possible within the timeline of your inquiry.

Australia is currently facing significant labour market shortages, with the lowest unemployment rate and highest participation rate for many decades.[1] This is particularly true in Western Australia, where a resource boom and a shortage of affordable housing is currently super-charging the state’s boom-bust cycle.[2] To complicate matters, these shortages are occurring during a period of rising inflation which is pushing up the cost of living, while wage growth is remaining stubbornly low and well behind CPI – challenging many of our assumptions about the relationship between labour force demand and wage growth.

Jobs and Skills have been identified as a national priority, and key stakeholders have been invited to a summit in Canberra to tackle our current economic and labour force challenges.[3] Meanwhile the WA Premier has launched an advertising strategy to attract migrant workers to WA and announced an extended list of VET courses with subsidised fees.[4]

Training and migration take time, and so the critical question for policy makers now is what can be done in the short-term to remove participation barriers for those who have skills and experience, but are not working to their full potential? Foremost among these underutilised cohorts are women of working age, particularly mothers, but also including those with other family caring responsibilities.[5] Hence one of the most critical emerging issues for workforce participation and economic productivity in the current debate is access and affordability of social care services, particularly childcare.[6]

We suggest that stronger focus is needed in on-the-job training and effective workplace supervision within human services, as many of the interactional complexities of these roles are not easily or effectively taught in classrooms but require real life experience. Greater recognition and support for experienced staff to take on supervision and mentoring roles will result in both improved service quality and improved workforce retention. When it comes to critical areas such as aged care and early childhood education and care the capacity of organisations to take in and upskill new workers is increasingly limited by the loss of experienced staff with supervision skills, who have been leaving these sectors for more secure and rewarding employment in other sectors. Hence a strategy based predominantly on new recruitment is inherently limited if more effort is not also put into retaining skilled staff and upskilling them.

Any effective workforce strategy must include a commensurate focus on job security and staff retention across key industries, especially in the health care and social assistance sector. With unemployment currently at record lows and critical worker shortages in key industries, there is now a strong focus on increasing workforce participation among under-represented and excluded cohorts – including attracting parents (predominantly mothers) and family carers (also predominantly women) back into the workforce, as well as encouraging and enabling those with care responsibilities to take on more hours, and supporting greater workforce participation among people with a disability. Before such strategies can succeed, the barriers to increasing workforce participation arising from existing and emerging problems within the Care sector need to be addressed – as discussed further below.

Retention is the single biggest challenge for community service organisations in the current economic cycle, as the combination of slow sector wage growth and insecure employment contracts (a knock-on effect of ongoing short-term and last minute funding contract rollovers arising from machinery of government changes – which should eventually be fixed by the WA State Commissioning Strategy[7]) has led to significant numbers of skilled staff to leave the sector for better paid public sector or private sector roles.

Though it is imperative to focus on skills and training, we must follow the pipeline through to job design and job quality, ensuring that the nature of jobs in Australia supports worker retention and wellbeing. This, in turn, ensures that employment in Australia is attractive for workers, meets community expectations around workplace conditions and ultimately delivers higher quality services with better community outcomes. WACOSS has welcomed recent WA Government investment in workforce training and skills development, particularly in the critical areas of mental health and alcohol and other drug services. We support the fostering of stronger links to and pathways from education to training institutions and work placements that reduce barriers to employment for cohorts under-represented in the workforce. We suggest that on-the-job training is critical to successful human service delivery and believe there is an untapped resource of people with lived experience who are currently under-represented in our workforce yet are able to bring compassion and insight to caring roles. We recommend a targeted program to provide incentives and support.

Developing and sustaining a skilled community services workforce to meet projected need is becoming an increasing challenge, given the existing gap in skills and workforce capability across a number of service areas and a tightening funding environment. Safe, effective, connected, person-centred community services require a skilled, competent and proactive workforce with appropriate qualifications and experience to deliver high-quality services; these jobs cannot be automated. The diverse skill sets to meet industry needs in WA has been outlined by the WA State Training Board in their Future Workforce Skills Report.[8]

Addressing the skilled worker shortage in the community services sector, requires strategic investment to attract workers, not only through education, training, and qualifications, but also through improved wages, job security, workplace conditions and career pathways. Without such investment, the community service sector will experience significant impacts on their capacity to retain skilled workers and to service the increasing complexity of need spreading throughout our communities.

Our discussions with younger workers entering and leaving our sector highlight that many have a calling to work in care services and make a deliberate choice to be part of “the wellbeing workforce” because they want to make a difference. Those leaving talk of being burnt out and feeling undervalued, struggling with short-term contracts and financial stress, and feeling like the lack of certainty prohibits them from building a career and securing a mortgage.

The current retention crisis highlights fundamental flaws in current funding models that suggests the marketization of services and transactional models of care have failed to meet the needs of both service users and care staff – as discussed further below. We argue that there is both an opportunity and a growing need to put ‘care’ back at the centre of our service system and focus on the true value of the outcomes delivered by relational service models. Service users and their loved ones clearly articulate that what they value most is service continuity and care – having an ongoing relationship with someone who understands the challenges they face, cares about them and is committed to working with them to make a difference.

This issue is at the core of the current crisis in aged care and home care services – as discussed further below. Increasingly insecure employment arrangements together with experienced staff leaving the sector and high rates of absenteeism has led to a reliance on casual and employment agency staff, so that care users and their families never know who is going to turn up at their door at what time. The combination of new carers with little knowledge or background on the needs, preferences and barriers faced by care users leads to poorer quality care, poor communication, and increasing risks of negative incidents, with core supports and risks missed, or errors made with medications. The development of national wellbeing budgeting frameworks arising from the October budget commitments creates an opportunity to measure what matters in service outcomes, shifting the focus from transactional activities to meaningful quality care outcomes.

It is important that the way we respond to workforce development and retention issues is well-targeted and evidence based. There can be a tendency to talk about ‘skills shortages’ when we have a tight labour market and particular sectors are less able to attract or retain skilled workers – there may not be an absence of workers with the necessary qualifications and experience across the workforce, they may simply be choosing not to use those skills given better opportunities elsewhere (i.e., a labour shortage, or a shortage of willing workers).[9] Simply focusing on more training places and incentives in the VET and tertiary sectors without considering retention and career development may ultimately merely increase the churn rate.

In a tight labour market, we need to be increasingly focusing on increasing the workforce participation rate by addressing the barriers to work faced by key groups currently excluded from the labour force – including single parents & working mums, skilled seniors, people with a disability, Aboriginal and migrant LBOTE workers, those on humanitarian visas and the under-employed. Tackling these barriers will require changes and better targeting of policy at state and federal levels complemented by personalised support provided by local community services with knowledge and experience working with these marginalised cohorts.

The evidence is clear that current labour force shortages in Australia are structural in nature and likely to persist for some time.[10] In the medium to longer term we also face the impact of an ageing population, with a declining proportion of those currently considered ‘of working age.’ This suggests we may also need to find more creative ways to encourage those of retirement age to participate on a part-time or flexible basis. A strategy that addresses the financial and regulatory barriers to participation[11] as well as providing employers with the tools needed to engage and support this skilled workforce could see Australia lift its current participation rate from 12 per cent to the 24 per cent achieved in New Zealand.[12]

Our response to the COVID crisis demonstrated the productivity outcomes of working from home, potentially opening up opportunities for people living with a disability to increase participation in the workforce, however we have yet to see a meaningful shift in their participation rate from 53 per cent.[13] An integrated strategy that engages employers to realise the opportunities to employ people with a disability, backed by the right kind of transitional support for both managers and workers could have a transformative impact and unlock significant unused potential. Australia has fallen behind our OECD counterparts on disability employment. We should be investing now in a world-leading national strategy to increase disability employment outcomes, with targets set for all public services, and reporting captured in the new Federal Budget wellbeing outcomes framework to be developed in 2023.[14]

Another group with significant unused potential is migrant workers and humanitarian migrants who have qualifications, skills and experience that are currently not recognised here, or where short-term support to transcend language barriers could unlock significant unrelated work skills.

One place where the WA Government has made important first steps to unlocking the workforce potential of an excluded group with significant skills to offer is through the development of its 2018 Aboriginal procurement policy[15] (with participation requirements extended in 2021[16]) and Aboriginal Community Controlled Organisation Strategy.[17] The ACCO Strategy prioritises the commissioning of culturally secure services for Aboriginal children, families and communities that are place-based and locally led, increasing employment of local Aboriginal people with lived experience and insight, who are better able to connect with the challenges faced by their communities.

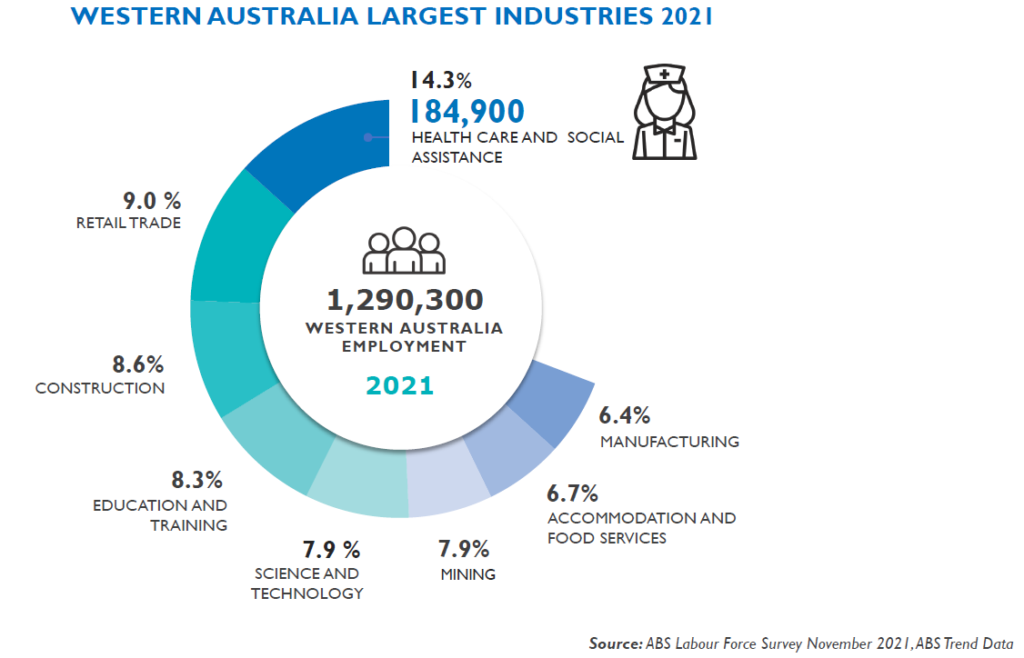

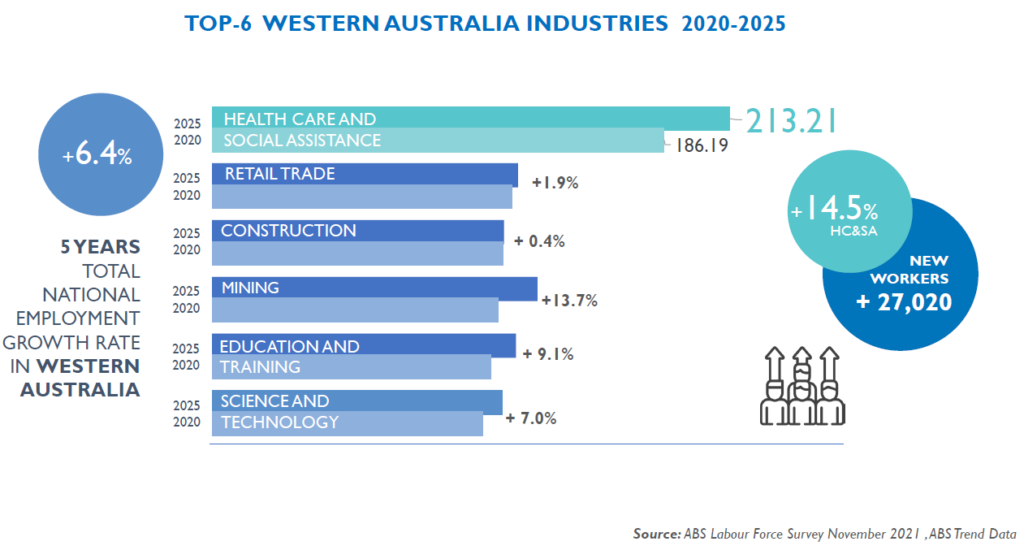

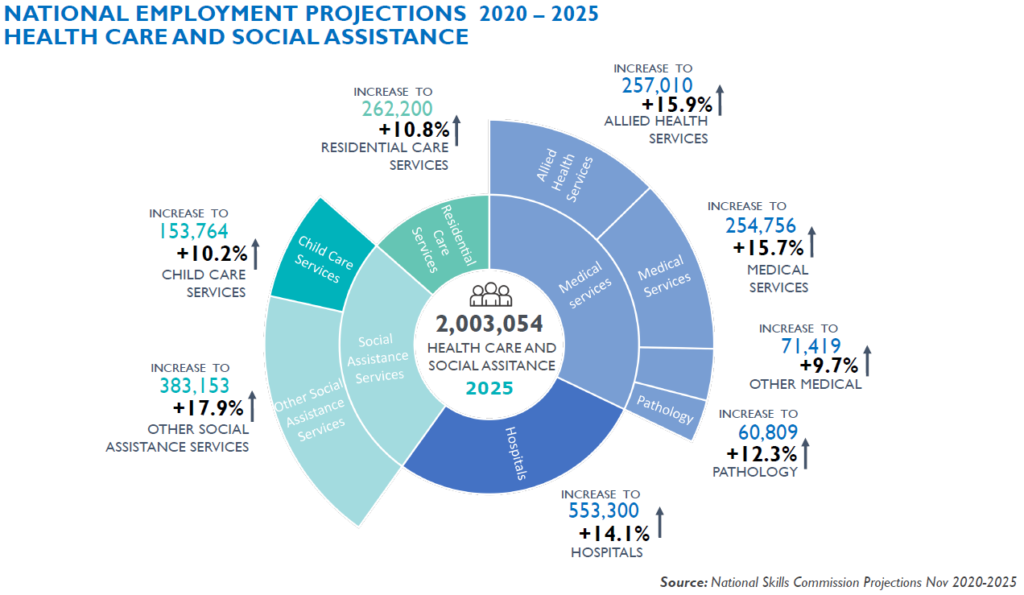

The evidence on the scale, impact and projected future growth of the health care and social services workforce indicates that it is both the largest and fastest growing employment sector in Australia and WA – employing 14.3% of WA’s workforce (184,900 people as of November 2021) and projected to grow by 14.5% by 2025 (requiring an additional 27,000 workers).[18] This means that we will need to be training more skilled workers through both VET and tertiary sectors and retaining and up-skilling existing workers and bringing in a migrant care workforce from the developing world over the next decade – to meet the needs of an ageing population and address projected demand in childcare, disability and aged care services. Other developed nations face exactly the same population ageing challenges and will be competing for migrant workers. In this context we need to be acting now to both develop training and immigration pathways as well as tapping into our own latent workforce capability, enabling excluded workers, changing attitudes to the care professions, and ensuring the work is more secure and rewarding.

The focus of this submission therefore centres on opportunities to better attract and retain workers and the systemic factors that contribute to worker shortages in the community service sector. Increasing retention rates through better job quality and training is a top policy priority to develop a skilled workforce, while broader factors such as affordable housing and placing a greater investment in community-based services must also be addressed, particularly in regional areas.

Addressing the Terms of Reference

The Senate Select Committee on Work and Care was appointed by resolution of the Senate on 3 August 2022 to inquire into the impact that combining work and care responsibilities has on the wellbeing of workers, carers, and those they care for. The committee will consider evidence on the extent and nature of work and care arrangements, the adequacy of current support systems, and effective work and care policies and practices in place in Australia and overseas. The terms of reference are repeated below:

- the extent and nature of the combination of work and care across Australia and the impact of changes in demographic and labour force patterns on work-care arrangements in recent decades;

- the impact of combining various types of work and care (including of children, the aged, those with disability) upon the well-being of workers, carers and those they care for;

- the adequacy of workplace laws in relation to work and care and proposals for reform;

- the adequacy of current work and care supports, systems, legislation and other relevant policies across Australian workplaces and society;

- consideration of the impact on work and care of different hours and conditions of work, job security, work flexibility and related workplace arrangements;

- the impact and lessons arising from the COVID-19 crisis for Australia’s system of work and care;

- consideration of gendered, regional and socio-economic differences in experience and in potential responses including for First Nations working carers, and potential workers;

- consideration of differences in experience of disabled people, workers who support them, and those who undertake informal caring roles;

- consideration of the policies, practices and support services that have been most effective in supporting the combination of work and care in Australia, and overseas; and

- any related matters.

We commend the Senate for establishing terms of reference for this inquiry that are timely and comprehensive. We have attempted to address all of the terms of reference within our areas of expertise and point to trusted sources of knowledge and insight where possible. Our particular focus is on items (2), (4), (7) and (9), with reference to data and analysis on (1), (5) and (6) from trusted sources. We agree that (3) and (8) are also important issues for the Senate to consider but lack the capacity and expertise to provide recommendations in those areas at this time.

Our hope is that, as a result of considering these issues of the relationship between work and care for the productivity and wellbeing of our workforce together with the opportunities to include those who are under-represented in our workplaces and marginalised within our economy, the committee will arrive on a position on the true value of caring to participation within and the health of our society. We suggest that a consideration of care ethics[19] that puts the care relationship back at the centre of our social service and welfare systems can provide the basis for a more productive, resilient and inclusive community, that is better able to meet the challenges of an uncertain future. Better understanding and valuing care in both work and life is also integral to addressing existing industry-level gender pay equity issues for female-dominated care industries, as well as rebalancing care roles and responsibilities across families and communities to ensure women’s contributions are valued, supported and celebrated appropriately.

The Care Workforce in WA

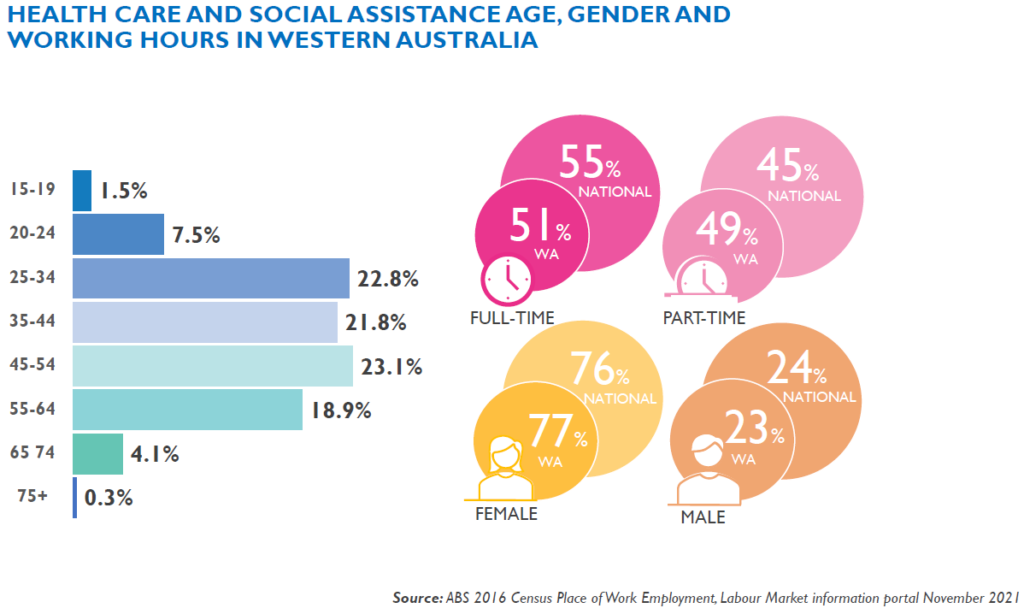

The WA health care and social assistance workforce is highly feminised, with 79% of the workforce female. [20] By comparison to the national average, WA has fewer HC&SS workers in fulltime work (51% vs 55%) and more in part-time roles (49% vs 45%). The workforce is also ageing, with 45% of workers aged over 45 years and 22% over 55 years.[21] The female underemployment rate for WA women also remains heigh at 8.76% (vs 5.2% for men).[22]

Adequate, sustainable funding for the community service sector

Fluctuating government funding, greater demand for services, and an increasingly competitive tendering environment are increasing financial pressure on the not-for-profit community services sector, which in turn impacts employment opportunities and retention of staff. Unlike other areas of public service delivery such as education and health, that are founded on policies of universal entitlement and population or demand-based funding, social services continue to rely on ad hoc program-based funding models that seldom keep pace with community need or the true cost of service delivery. The uncertain funding environment constrains job security and employee confidence for their immediate future.

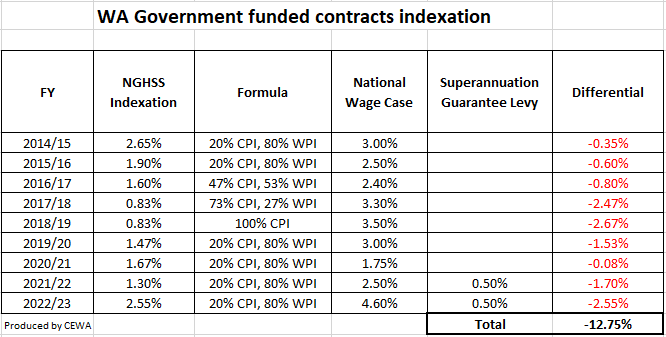

In addition, a significant gap between funding indexation and direct labour cost increases has been a consistent trend for community organisations for years in WA, as service contracts have continued to be rolled over rather than recommissioned. WA State Government indexation of 3.53% under the Non-Government Human Services Sector (NGHSS) Indexation Policy will be applied to community sector funding for the 22/23 financial year.[23] This level of indexation does not reflect the true increased costs for organisations, especially in light of the recent Federal and State award wage announcements. Perth CPI was 1.7% for the June quarter and 7.4% for the year to date, compared to 6.1% nationally.[24]

The Western Australian Industrial Relations Commission announced a 5.25% increase to the State Minimum Wage and a 4.65% increase to WA Awards in its 2022 decision on the State Wage Case. Approximately 30 per cent of the WA community sector workforce is covered by the state system, and around 70 per cent by Federal Awards. When combined with the Superannuation Guarantee increase, the Fair Work Australia decision for the National Annual Wage Review results in a minimum 5.1% increase in labour costs for community organisations. Since the sector is comprised of people-centred social services, staff costs account for around 70-80 per cent of its running costs.

The difference between indexation and wage costs has been steadily growing over the last decade. Analysis estimates that this has resulted in a gap of 13.35 per cent to the real cost of service delivery.

Table 1. Differential in indexation and wages costs in WA Government funded contracts

Source: CEWA

Current trends in indexation may increase barriers to industry investment in training, create greater pressure for adaptability and the minimisation of labour costs, and limit opportunities for career development and higher-paid work, all of which have the potential to degrade jobs. The 2022 ACOSS Community Sector Survey revealed that only 14 per cent of community sector organisations across Australia reported indexation arrangements for their main funding source as adequate.[25]

Without an increase by the State Government to the 2022/23 NGHSS indexation, the impacts will include:

- Cuts in community services at a time when extremely high demand is out-stripping supply.

- Decreased job and income security for women, as 80 per cent of the community service workforce are women, with a very high risk there will be a cut in hours or reclassification of positions. The resulting loss of income will drive people out of the industry, especially in the current economic environment of rapidly rising inflation.

- Inability to provide training, mentoring support and personal development opportunities for staff due to lack of sufficient resources. This occurs at a time when there are real shortages of skilled care staff in social services within our state, and many have left to take up better paying work in other sectors.

- Inability to attract new workers to the sector.

Inadequate funding and indexation hold the sector in a low-experience vortex, with entry level workers unable to access ongoing training and skills development opportunities, and experienced workers choosing to exit the system because of the pressure associated with heavy workloads and low pay.

The new Federal Minister for Aged Care, the Hon. Anika Wells recently told ABC 730 Report that the Albanese Government was committed to funding a 25% pay increase for aged care workers if and when the fair Work Commission delivered their decision on sector wages (see also comments on ‘fixing aged care’ by the Prime Minister). A significant increase in pay within federally funded aged care services is likely to see a substantial number of workers in low-paid and insecure roles in state-funded services with similar skill sets choosing to change roles.

Recommendations:

- Indexation and resourcing of State and Federal contracts must be sufficient to ensure award obligations can be met

- Public authorities should contract with the not-for-profit community services sector in a manner that supports sustainable and effective service delivery and greater parity in pay and conditions for community services workers

On the job training

WACOSS commends the State Government’s commitment to providing low-cost vocational training in priority areas, and the promotion and development of skill sets to build the capability of the community services and health workforces, as outlined in the Strategic State Government Response to Social Assistance and Allied Health: Future Workforce Skills Report.[26] These commitments will help address financial barriers to education and training opportunities and spur commencements in training.

Further training opportunities to grow Western Australia’s community service sector workforce can be pursued by developing sustainable training regimes and expanding the capacity for skills growth in community service organisations and for their workers. This will require a multifaceted partnership approach between government and the sector that addresses on-the-job training barriers.

Taking a ‘skills ecosystem’ approach that recognises the interdependent nature of employers, workers and training providers in skill formation will help address the complexity of issues in developing and retaining a skilled workforce.[27] Expanding training opportunities in the workplace will help ensure that current government investment in expanding training opportunities with VET providers are not met with high attrition rates due to wider workplace conditions across the sector.

As previously highlighted, indexation rates and procurement models that force organisations to compete for limited funding, influences the propensity for organisations to provide training to new recruits and existing staff across the sector. Organisations must tightly balance how budgets and workloads are managed, particularly when servicing increasing demand, which limits expenditure and opportunity for investment in on the job training and mentoring. On the job training and mentoring, for example, is critical in the disability sector, yet NDIS funding fails to incorporate training of staff into funding models.

Wider workplace conditions, including high levels of casual and part-time work, high levels of unpaid work being performed by workers, and staffing shortages that inhibit meeting service demand, act as additional barriers to work-related training and professional development opportunities. The Community Services and Health Industry Skills Council outlines how the increasingly casualised and insecure nature of employment within the sector has resulted in training costs being shifted more directly on to the employee.[28] They note that as a greater proportion of care work is undertaken by women, it is women workers who tend to be excluded from opportunities for employer sponsored training, limiting career progression and higher-paid employment opportunities.

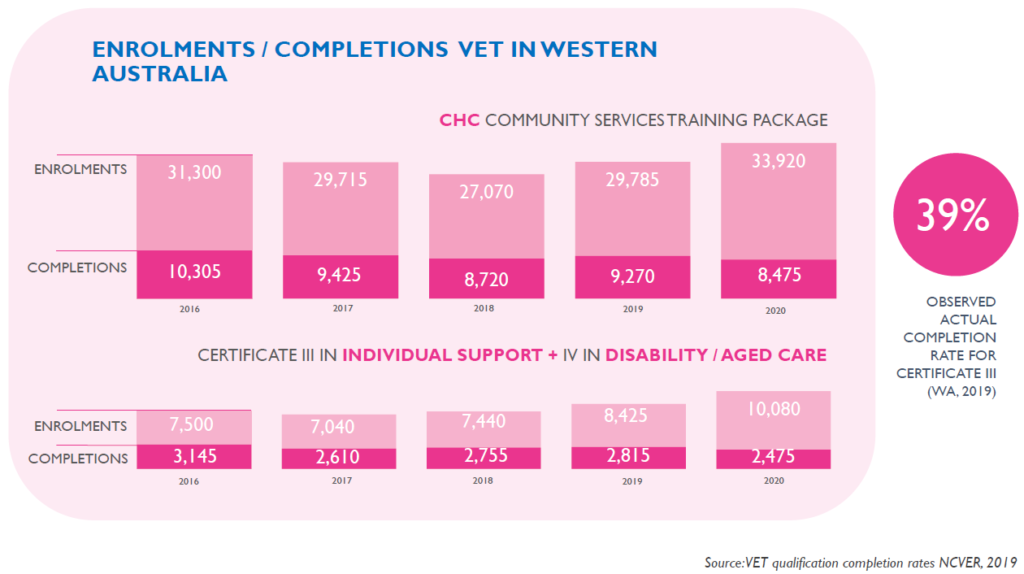

Evidence on community services training completions within the VET sector suggests that there is a comparatively poor completion rate, suggesting that significant numbers are attracted to a vocation in the caring professions, but are potentially dissuaded as they learn more about the roles.[29] More work is needed to understand the barriers to course completion, such as analysis of student intake and exit surveys, to determine what is dissuading students and to provide better incentives to complete training and take up employment within the sector.

There is a critical shortage of trainers and assessors across the community sector to develop and promote the skills sets to meet its needs. Training should be seen as a partnership between government, training providers and community service organisations, where organisations are supported and funded appropriately to provide on the job training and mentoring. Investing in on-the-job training and professional development provides workers with the space to continuously grow and learn, strengthens the delivery of safe, high-quality care and supports regulatory compliance in sectors such as aged, disability or childcare, among others.

Recommendations:

- Support greater links and partnerships between training providers and community service organisations,

- Recognise the importance of worker training in procurement policies

Aboriginal Community Service Sector Workforce Development

The gap in economic participation and life outcomes for Aboriginal people in Western Australia remains significant. The continued impacts of colonisation, racism and intergenerational trauma are sustained by harmful government policies and practices; health, education and support service systems that are inappropriate or inadequate to meet levels of need; poverty and lack of opportunity. Fear and a lack of trust in institutions also play a critical role in lower rates of access to universal and secondary support services, particularly when it comes to justice and child protection services that many families associate with both former stolen generation practices and current harms that have been perpetuated by agencies.

There is a strong need for a greater focus on Aboriginal employment in health, education and community services. Given the projected growth of the service and caring economy, and disproportionately high levels of need for services and support by Aboriginal families and communities, the development of a human services workforce offers an excellent opportunity for generating greater trust in services and for increasing economic participation, helping develop more sustainable and resilient local economies.

A planned and sustained strategy is needed to provide a coordinated approach supporting a skilled Aboriginal human services workforce, and build sustainable Aboriginal organisations and businesses by setting clear employment and training targets. The example of the State Government’s Aboriginal Procurement Policy, which quickly and significantly surpassed its mandated targets,[30] demonstrates how successful this kind of approach can be.

A combination of contracting requirements, additional incentives, and training support is likely to deliver the most effective outcomes. Contracts over a certain size should include minimum employment and training requirements, additional resources made available to leverage increased employment outcomes, and access to targeted support to ensure Aboriginal workers are work-ready, have access to additional training where necessary and their supervisors and co-workers have access to appropriate information and assistance.

There is a significant risk that a strategy that does not address these gaps and challenges would be setting up Aboriginal people, communities and community services to fail. There is a clear role for government to commission employment services at a local or regional level to provide appropriate support. Existing Aboriginal organisations are most likely to be best placed to deliver this support, with many Aboriginal community-controlled organisations having a strong record of outcomes in this area.

In September 2021, the State Government released its first Implementation Plan for Closing the Gap and the Aboriginal Empowerment Strategy. These documents provide the groundwork for a significant shift in the way that government has typically related to Aboriginal people in WA, with a new focus on empowerment, truth-telling, culture and country permeating the direction they set.[31]

The community services sector has a critical role in the delivery of these priorities, partnering with government to create systems and services that are culturally secure and safe, and significantly increasing the proportion of those services that are delivered by Aboriginal community-controlled organisations.

Recommendations:

- Develop an Aboriginal workforce development strategy that provides incentives and support to increase Aboriginal employment in human services contracts

- Establish requirements in State and Federal Government contracts to train and employ people within the local community with a focus on Aboriginal workers.

Early Childhood Education and increasing workforce participation

Childcare services are projected to increase by over 10% nationally between 2020 and 2025, requiring an additional 154,000 workers nationally and around 16,000 in WA. Higher rates of workforce development will be needed if we are to increase the workforce participation rate of women within the WA labour market (now up to 64.5%, vs 74.8% for men) and to increase the proportion of women working fulltime (51.5%, vs 82.6% for men).[32]

Increasing access to affordable and reliable childcare services has been advanced as the biggest way to boost participation rates to address current labour market shortages.[33] While more childcare is clearly on the agenda for the National Jobs & Skills Summit, there are significant workforce retention and recruitment challenges that must be addressed to increase care access.

Federal Labor have promised $1.1 billion to create 465,000 free TAFE places in 2023,[34] and Jobs & Skills WA has extended half price vocational training courses for a Certificate III in Early Childhood Education and Care, or a Diploma of Early Childhood Education and Care.[35] An estimated 40,000 additional early educators are needed to meet demand by 2023. While more workers are required and we are currently not training enough students to meet our growing workforce needs,[36] more trainees alone will not solve this problem.

Childcare may appear an archetypal example of a skills shortage, however systemic issues with low wages, increasing regulatory demands and insecure work have led many skilled workers to leave the sector. Unless we can retain and bring back skilled and experienced workers, we lack the capacity to take on and supervise more new graduates and meet mandated staffing ratios.

Hence childcare is a great case study of how we need to look beyond a one-dimensional analysis of ‘skills shortages’ or ‘worker shortages’ to take a more nuanced approach to addressing systemic issues to improve retention and increase childcare places.

The early education and care (ECEC) workforce play a critical role in both workforce productivity and community wellbeing. It provides both childcare services which enable parents (particularly mothers) to participate in the workforce, and it provides crucial early development, education and wellbeing to children during the critical early years – the most significant period of intellectual, social and emotional development that provides the foundations for life-long productivity and wellbeing. It is crucial that government policy on workforce, education and social welfare balance both the workforce participation and early development aspects of early learning.

A focus on the marketization of the provision of cheap childcare at the expense of sufficient care to support social and emotional development will cost us more in the long-term. It is arguable we are now seeing the generational impacts of inadequate investment in early development and care result in increased rates of anxiety, poor mental health and wellbeing in young adults who are now completing school and entering the workforce.

While many young people have a calling to early education and care, wages and conditions need to be competitive for them to go on to make it their career. Pay rates are low, while funding models have led to an increased reliance on insecure employment arrangements, increasing financial stress and leaving workers feeling undervalued.

TAFE or University-based training also only gets you so far in a profession that is very-much relational work, and much more on-the-job training is needed to attain a level of competency. Many new graduates find the experience of trying to ‘manage’ a room full of small, energetic, demanding little people overwhelming, leading to very high early drop-out rates.

Increased regulatory requirements aimed at ensuring service quality have raised the administrative burden, while mandated ratios for higher qualified staff have led to closures of rooms or entire services due to staffing issues, particularly in regional WA. While some mining companies are helping set up childcare services to address their workforce barriers in the north, childcare workers don’t make enough to rent in town. And we still hear stories of them being poached to go drive trucks…

An immediate boost to salaries with a clear signal that structural reform is underway to better value experienced workers would go a long way to attract back to the sector a skilled workforce in the short-term and quickly boost places. Early education and care can offer more promising career options, increasing responsibility and remuneration over time through mentoring and supervision roles delivering much-needed on-the-job training.

There are currently significant barriers to childcare availability and affordability within WA that are creating barriers to women’s workforce participation and acting as a brake on our economy. This is particularly true in regional areas, where a lack of services and the inability to attract and retain skilled staff is at crisis point. Regional centres in the northwest in particular cannot secure ECEC staff, as higher living costs and a lack of affordable local housing have become significant barriers. While local services have been partnering with the resource sector in regional centres in the Pilbara and Kimberley to come up with interim solutions, there is a need for longer-term systemic solutions to support and enable regional development. Childcare availability is also a significant barrier to regional development and workforce participation in the Midwest and Southwest regions, where similar private sector partnerships to set up facilities or access subsidised housing re not an option.

In the medium term more work is needed on funding and regulatory reform to better ensure both service viability and care quality, particularly for services in regional and remote areas or those supporting more disadvantaged populations. We need to see more in-reach from training and professional development providers, backed with some targeted funding to up-skill capable staff to take on broader roles. The Victorian Government has developed an innovative accelerated teaching course for experienced educators in early learning that could serve as a model to ‘grow the pipeline’ of teachers in our state.[37]

Policy and funding need to balance early development outcomes with workforce participation to deliver the best productivity and wellbeing outcomes in the longer term. This recognises the role of early years services in social and emotional development and self-regulation during the critical first five years of life, where the majority of brain development occurs.[38] Hence, we prefer the language of ‘quality early childhood education and care’ (ECEC) to talking about ‘childcare’ as implying the cheapest cost child-minding to enable women’s workforce participation.

Recent surveys of childcare workers indicate that a high proportion of current workers are dissatisfied with job insecurity, pay and conditions as well as working conditions and future prospects, and intend to leave the industry.[39]

ECEC providers have reported to the Children’s Policy Advisory Council that they face significant capacity constraints in taking on newly graduated staff, without sufficient experienced staff capable of providing ongoing supervision. The sector is concerned that the focus of workforce policy in this area appears to be largely on VET sector training student intake, while ignoring the need to retain existing experienced staff and to provide sufficient support for on-the-job training and upskilling the existing workforce. Service managers caution that unless something is done to address the current retention crisis and reduce the numbers currently leaving the sector, providers may be unable to meet mandated ratios and ensure adequate supervision. Without the experienced staff, childcare centres are not able to meet their compliance requirements and taking on new students is not an option to address this challenge alone, given the ratios and the need for experienced supervisors.

The role of early childhood educator needs to be promoted and recognised for the critical impact it has child’s development (and workforce participation and productivity) and mechanisms established where the experienced workers are offered appropriate levels of remuneration and access to ongoing professional development (including backfill as needed to be able to participate). An effort needs to be made to attract skilled and experienced workers back to the sector to have a more immediate impact on workforce participation in the short-term, while longer-term workforce development policies are implemented.

Western Australia faces some unique challenges in responding to recent national preschool funding reform commitments to ensure our ECEC sector is fit-for-purpose and addressing both participation and early development quality challenges. In relation to increasing workforce participation, the current system divides care between the hours provided through school-based preschool centres delivered through the Department of Education, and the actual hours of care needed by working parents – who then also need to access community-based care and/or long day-care to ensure their children are cared for and safe during work hours. Changes to mandatory entry requirements and qualifications may also result in barriers for existing skilled workers who need to upskill or re-qualify to maintain employment, but do not have access the professional development support required.

Those currently excluded from the workforce face systemic barriers to sourcing accessible and affordable childcare. Single parents seeking work are often caught in a Catch 22 scenario, as they need sufficient hours of reliable care to start work, but approval processes and wait lists can mean by the time they secure care they have missed the job offer. Single mothers have the highest rates going in and out of part-time work of any group on income support due to these problems. Abolishing the activity test for the childcare subsidy would directly benefit 126,000 children in our most disadvantaged families and boost workforce participation.[40]

Free access to quality early learning and care is arguably the single biggest thing we could do to address early developmental vulnerability and deliver lifelong wellbeing outcomes. Happy and well-regulated kids make for a skilled and productive future workforce – it is a high return investment with a long lead time.[41]

Western Australia in particular, faces challenges ensuring our early education and care system is fit-for-purpose. Our system is complex, and the split between subsidised pre-school services delivered by the education system and the community-based care services needed to fill the gap between the care hours and parental work commitments.

WA has signed up to the National Preschool Reform Funding Agreement,[42] but faces a significant policy challenge to meet its’ targets for care hours. In 2020 there were 34,000 children enrolled for 600 hours of ECEC in the year before school, of which only 23,400 or 70% attended the full 600 hours. 76% enrolled in preschool only, 3% in long day care only, and 22% in both. Only 59% of those enrolled in state preschool met the target of 600 hours.[43] In other words, parents rely on access to unfunded long day care to work, and the State now also needs after school care hours to meet its targets – requiring the kind of subsidies we see in other states.

Increasing workforce participation can deliver an economic advantage and boost our productivity, supporting the diversification and resilience of our economy. Other states are investing heavily in early education and care independent of Commonwealth arrangements,[44] with per capita grants to support participation, teacher supplements to promote pay parity, and targeted assistance for disadvantaged areas and vulnerable cohorts. If WA wishes to remain competitive, we need to look at what works in other jurisdictions, to see what we can adapt and adopt to deliver better outcomes for our children, families and workplaces.

Recommendations

- Encourage and support early childhood centres to provide on-site training and professional development and provide scholarship funding to up-skill experienced staff to provide supervision and mentoring.

- Develop policies and incentives to retain existing skilled early education and care staff, including greater job certainty and improved employment conditions.

- Prioritise the development and provision of childcare services in regional areas as a key support for regional development outcomes.

- Address barriers to childcare access for parents seeking work, particularly single mothers.

- Progress universal access to quality education and care as an economic development priority.

Labour market trends across care industry workforces

There is a significant amount of work that has been done in relation to the workforce development needs of the aged care and disability sectors, and recent national inquiries and Royal Commission have highlighted significant challenges in relation to quality and sustainability of services.[45] We expect that detailed submissions will be prepared by the relevant industry and consumer peaks on workforce issues in these sectors. In relation to current labour market trends, we recommend the Bankwest Curtin Economic Centre (2022) Population, Skills and Labour Market Adjustment in WA report as an up-to-date source of reliable information and analysis.[46]

WACOSS members are concerned by the broader longer-term workforce trends that have emerged over the last decade or more across the aged care, disability and childcare workforces. We believe that there are fundamental underlying structural changes that have occurred to the labour market for the care industries that have been driven by government policy, regulation and funding levers that have undermined both the quality of employment conditions and service outcomes. Human service quality and sustainability has been undermined by service marketisation and individualised funding models, in a manner that is increasingly enabling the exploitation of insecure workers and enabling third-party labour hire agencies to profit, while mission-driven not-for-profit providers lose staff and become increasingly unviable. Gig-economy platforms such as Mable are able to circumvent the regulatory costs and requirements placed on traditional aged and disability care employers in a manner that reduces costs and responsibilities. The end result however, for service users and their loved ones, is lower quality and less reliable services.

When it comes to caring and support services, such as early childhood education and care, or home and community care, service users and carers want and highly value a meaningful and ongoing relationship with the care provider. Quality and consistency of care is predominantly relationship-based, it is important that the care providers know and understand their needs and circumstances and that they feel that they actually care. An increasingly casualised and varying workforce, where workers are interchangeable, time-poor and stressed, and must rush from job to job to meet deadlines does not deliver the kind of services the community expects and values. Increasing use of platform-based care is a clear and emerging trend, but it is unclear how well the impacts of this mode of delivery are captured in agency reporting and regulator quality oversight. Service providers report their staff are increasingly choosing better pay and the promise of flexible hours, over ongoing employment under existing funding and award arrangements. As a result, they are finding it hard to recruit new skilled staff and have to increasingly rely on agency staff to meet care commitments, which costs the service more and undermines their ongoing viability.

Australian Governments continue to take a narrow view of productivity that undervalues the work of female-dominated care industries, based on a narrow analysis of gross value added that would have us believe a worker making a chocolate bar is making a greater contribution than one educating a child (as was mentioned in the Jobs & Skills Summit). When considering the contributions of an early educator in a childcare service, their contribution to our economy and the wellbeing of the community should also include the additional contribution made by a parent or parents who are freed up to work and less stressed because they know their loved ones are doing well … as well as the future contribution that a happy, healthy and well-regulated child can make as a creative and productive future worker. Developing better measures of productivity as part of an approach to measuring what matters should enable a more accurate and informed appreciation of the contribution of care to work and wellbeing, that may lead governments to move from considering care services and welfare spending as a ‘sunk cost’ and ongoing burden, to an economic multiplier and key component of community health.

Recommendations

- Develop collaborative reform approaches to service delivery and funding models in aged care, disability and childcare services through COAG as a national priority.

- Prioritise secure work arrangements and continuity of care across human services.

- Pursue industry-level gender equity outcomes through Fair Work Australia.

- Develop productivity metrics that capture the true value of care service including, for example, the additional participation and productivity of family carers and the future productivity of healthy well-educated children as adults.

Housing

WACOSS recognises the government’s efforts at attracting skilled interstate and overseas workers to live and work in Western Australia. However, efforts to attract interstate and overseas workers without consideration of where these workers will be able to affordably live is a vital piece missing from the strategic plan to address the state’s skilled labour shortage. Rising rents and a lack of rental properties and affordable housing across Western Australia already has a range of implications for low- to middle-income earners, particularly in regional areas.

In many regional communities, community services cannot keep pace with demand for services, with workforce shortages exacerbated by low-paid, short-term contracts and high cost of living. Attracting and retaining staff is extremely difficult in regional areas as salary packages do not cover housing and rental costs, which are prohibitively high in towns that also service a large number of the fly-in fly-out mining workforce.

With essential services being delivered in regional areas predominantly through short-term contracts and relatively low annual salaries compared to mining or government salaries, the lack of job security coupled with the high cost of living is not only undesirable for most workers, but financially untenable. Insecure, inappropriate and unaffordable housing in regional areas intersects with insecure and precarious work to create barriers to regional employment that limit regional growth and exacerbate boom and bust cycles in regional towns and centres.

In both regional and metropolitan areas, many workers in community services perform physically and emotionally demanding jobs, work long shifts, work during anti-social hours and/or work in high stress situations. Housing stress and insecurity can exacerbate the stress and fatigue resulting from performing their essential duties. That, in turn, can negatively impact service quality, including through an inability to retain more experienced workers in the long term.[47]

WACOSS recognises the government’s action to freeze rents on public sector housing in regional WA to support worker retention. A focus is also needed on improving access to housing for workers in the NGO community service sector. Across Australia, there have been limited federal or state housing programs or policies specifically designed to support key workers outside of the public sector to access housing or the delivery of affordable housing for low- and moderate-income earners.[48]

Housing All Australians Give Me Shelter report found that the national average benefit-cost ratio for Australia in providing adequate social and affordable housing infrastructure is 2:1.[49] Not only is there is a strong underlying business case to create more public, social and affordable housing supply, but also a clear rationale to address housing affordability and availability as part of any effort to attract workers into the state, particularly in regional areas.

Recommendations

- Develop housing initiatives that ensure provision of accommodation for employees of Non-Government Organisations (NGOs) contracted and funded by the State or Federal Government to provide key services in regional locations

- Incorporate housing costs into service delivery contracts in high-cost regional locations to sustain the delivery of funded NGO services

Recognising the community sector’s value and contribution

It should be noted that the term skill shortage is often a surrogate term for more general recruitment and retainment difficulties in the community service sector. It is unlikely to be possible to attract and retain sufficient workers to meet the growing demand unless pay and working conditions change. Improving community service sector job quality and conditions would also improve quality of care and reduce turnover costs.

It is widely acknowledged that care-giving remains devalued in both social and economic terms. In real terms, the wages associated with performing care work are lower than other forms of work requiring comparable qualifications or skill, and this remains a significant deterrent to attracting and retaining workers for the sector. Workers are consistently poached from the NGO sector by government agencies and the mining sector, particularly in regional areas, who can offer significantly better pay, along with greater job security, and clearer protections for working hours. This is particularly common for the ACCHO sector.

As previously highlighted, the majority of roles within the community service and health settings are held by women, but roles in the sector are increasingly being portrayed as a less attractive option than STEM, Construction or Mining. This is damaging, and can actively discourage people from entering the community service sector workforce. Public perceptions of care work need to be lifted and the extraordinary contribution of workers in caring for Western Australians better recognised and rewarded. Those who chose to pursue roles that involve caring for others should not be made to feel like that are taking a less challenging or valued pathway.

The community sector has immense expertise to offer government, and this has been especially valuable as Australia responds to the multi-faceted crises posed during the pandemic. A collaborative approach between sectors could include mentoring, supervision and personal development that even encourages sharing of staff across sectors and industries (such as Allied Health Professionals), which may assist with attraction of staff to regional areas and enable ongoing professional development.

The wellbeing workforce: a strong investment case

While we often think of mining and construction as the pillars of our state’s economy, health care and social assistance is the largest employing industry in Western Australia and is projected to grow faster than any other area of the economy over the next five years.[50]

Researched commissioned by the International Trade Union Confederation found that if Australia invested 2 per cent of its GDP in the care industry, it would directly create 356,812 new jobs and raise the employment rate by 2.3 per cent.[51] When both the indirect effects through the supply chain and the induced effects from increased demand within the economy are added, this sees the creation in Australia of 613,597 new jobs and a rise in the employment rate of 4 per cent.

In comparison, the same level of investment in construction only directly increase the employment rate by 0.5 per cent and by 2.5 per cent when indirect and induced effects are taken into account.

Investing in the care economy also has a profound impact on closing the gender employment gap, with the modelling showing that 79 per cent of the new jobs created by this level of investment would be taken by women, increasing the employment rate for women by 3.7 per cent and decreasing the gender gap by 2.6 per cent. This far outpaces what would be seen in the construction industry, where only 11 per cent of the jobs would be taken by women and their employment rate would rise by just 0.1 per cent.

Importantly, investment in community-based services that focus on prevention and early intervention will reduce the pressure on the health care system, helping to alleviate critical staffing issues, reduce the cost burden and improve health outcomes.

Recommendation

- Targeted transitional investment in job creation and training in areas of unmet and growing need, such as aged care, disability services, FDV services, ACCO services.

—

For more information on this submission you can contact Chris Twomey, Leader Policy and Research, via [email protected]

References

[1] Latest ABS Labour force data at: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia-detailed/latest-release

[2] Latest ABS Labour Force data for WA: https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/employment-and-unemployment/labour-force-australia/latest-release#states-and-territories

[3] Treasury (2022) Jobs & Skills Summit Discussion Paper. https://treasury.gov.au/publication/2022-302672

[4] Premier Mark McGowan media statement (2022) also training assistance announced.

[5] Bankwest Curtin Economic Centre (2022) Population, Skills and Labour Market Adjustment in WA https://bcec.edu.au/publications/ Figure 20, page 73, Figure 26, page 79.

[6] BCEC (2022) Op Cit. Figure 28, page 80, Figure 29, page 81.

[7] Government of Western Australia (2021) State Commissioning Strategy. https://www.wa.gov.au/organisation/department-of-finance/state-commissioning-strategy-community-services

[8] Government of Western Australia (2022) Strategic State Government Response to Social Assistance and Allied Health: Future Workforce Skills Report.

[9] BCEC (2022) Population, Skills and Labour Market Adjustment in WA. Op. Cit. Page 56.

[10] Treasury (2022) Jobs & Skills Summit Discussion Paper https://treasury.gov.au/publication/2022-302672

[11]Including aged pension income thresholds, simplified reporting requirements and reduced compliance risk.

[12] See NZ Gov (2019) Review of retirement income policy.

[13] We ranked 21 out of 29 OECD countries in 2015: See also: OECD Report.

[14] Treasurer Jim Chalmers (2022) statement July 18. See also https://theconversation.com/wellbeing-its-why-labors-first-budget-will-have-more-rigour-than-any-before-it-187160

[15] WA Gov (2021) General procurement direction,

[16] WA Gov (2021) Participation requirements Aboriginal procurement policy

[17] WA Gov (2022) ACCO Strategy 2022-32

[18] ABS Labour Force Survey November 2021, ABS Trend Data.

[19] See for example Stephanie Collins, (2021) The Core of Care Ethics, or ABC RN (2021) Why we should care about ‘care ethics’.

[20] WA Women’s Report Card 2022. BCEC and Department of Communities

[21] ABS 2016 Census Place of work, employment, labour market information (November 2021)

[22] WA Women’s Report Card 2022, op cit.

[23] Department of Finance (2022) NGHSS Indexation. Community Services Procurement Bulletin.

[24] ABS (2022) Consumer Price Index Australia.

[25] Cortis N and Blaxland, M (2022) Carrying the costs of the crisis: Australia’s community sector through the Delta outbreak. Sydney: ACOSS

[26] Government of Western Australia (2022) Strategic State Government Response to Social Assistance and Allied Health: Future Workforce Skills Report.

[27] Community Services and Health Industry Skills Council (2012) Identifying Paths To Skill Growth Or Skill Recession: A literature review on workforce development in the community services and health industries. Industry Skills Councils: Australia. (see also the Future Priority Skills Resource)

[28] Ibid.

[29] NCVER (2019) VET Completion rates.

[30] Hon Ben Wyatt (2020) ‘Government’s Aboriginal procurement exceeding expectations’, Media Statements, Government of Western Australia

[31] Hon Stephen Dawson MLC (2021) ‘State Government releases Aboriginal Empowerment Strategy and Closing the Gap Implementation Plan’, Media Statements

[32] WA Women’s Report Card 2022. BCEC & Department of Communities.

[33] For example, https://www.smh.com.au/politics/federal/jobs-summit-needs-to-solve-childcare-crisis-to-tap-into-workforce-of-women-20220812-p5b9gs.html, https://www.afr.com/politics/federal/chalmers-sets-ground-rules-for-jobs-and-skills-summit-20220817-p5bahb.

See also Treasury Jobs & Skills Issues Paper https://treasury.gov.au/publication/2022-302672

[34] https://www.alp.org.au/policies/fee-free-tafe-and-more-university-places

[35] https://www.jobsandskills.wa.gov.au/pathways#early-childhood-education-and-care-job-ready-program

[36] https://thrivebyfive.org.au/news/the-parenthood-jobs-and-skills-summit-must-address-workforce-crisis-in-early-childhood-education-and-care/.

[37] https://www.vic.gov.au/innovative-early-childhood-teaching-courses

[38] https://bcec.edu.au/publications/the-early-years-investing-in-our-future

[39] See for example https://theconversation.com/early-childhood-educators-are-leaving-in-droves-here-are-3-ways-to-keep-them-and-attract-more-153187 Also childcare workers industrial action 6 September 2022.

[40] Impact Economics and Policy (2022). Child Care Subsidy Activity Test: Undermining child development and parental participation.

[41] https://bcec.edu.au/publications/the-early-years-investing-in-our-future

[42] https://www.dese.gov.au/child-care-package/preschool/preschool-reform-funding-agreement

[43] ABS 4240.0 Preschool Education Australia (2020) Table 28.

[44] https://earlychildhood.qld.gov.au/news/educators/new-kindy-funding-reform-package-for-queensland

[45] For example ACIL Allen (2021) The economic and social impact of the aged care sector in Western Australia

[46] See BCEC (2022) Population, Skills and Labour Market Adjustment in WA. The report is due to be released the day after submissions close. https://bcec.edu.au/publications/

[47] Gilbert, C., Nasreen, Z. and Gurran, N. (2021) Housing key workers: scoping challenges, aspirations, and policy responses for Australian cities, AHURI Final Report No. 355, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute Limited, Melbourne.

[48] Ibid.

[49] SGS Economics and Planning for Housing All Australians (2022) Give Me Shelter: The long-term costs of underproviding public, social and affordable housing. Shelter WA

[50] State Training Board (2019) Social Assistance and Allied Health Workforce Strategy

[51] Jerome De Hanau, Susan Himmelweit, Zofia Tapniewska and Diane Perrons (2016) Investing in the Care Economy: A gender analysis of employment stimulus in seven OECD countries, UK Women’s Budget Group, International Trade Union Confederation