WACOSS supports the call from the National Association of Renters’ Organisations, National Shelter, Everybody’s Home and Better Renting for National Cabinet to coordinate the following:

- An end to no cause terminations, including at the end of a fixed term;

- Reforms to stabilise rent prices including by setting clear limits for rent prices and increases;

- Minimum energy efficiency standards for rental homes; and

- Enhanced frameworks to support compliance and introduce accountability for non-compliance with existing laws, including around privacy. [1]

In addition, WACOSS recommends:

- Significant and sustained investment to increase the stock of social housing;

- Supporting tenants in financial hardship through rent relief grant schemes;

- Implementing inclusionary zoning with social and affordable housing targets;

- Establishing a vacant residential property charge;

- Stronger regulation of short-term rental accommodation;

- A target of zero children evicted to homelessness from public housing; and

- Increasing the rates of JobSeeker, Commonwealth Rent Assistance and other associated payments to above the poverty line.

A System in Crisis

For people to be able to fully engage in our community, it is fundamental that they have access to safe, secure and affordable shelter. Stable tenancies are crucial to support positive outcomes in areas like health and wellbeing, education and employment. Conversely, insecurity and instability in housing creates the circumstances for increased hardship and entrenched disadvantage.

It is for these reasons that access to housing is a basic human right. Maximising rental returns as a landlord, however, is not. The community should be able to have confidence that the rental market is providing liveable, affordable, stable housing where people can happily make their home. Unlike in Australia, this key fact is recognised in the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, which states that ‘property entails obligations. Its use shall also serve the public good.’[2]

We should not accept or allow the continuation of a system in its current condition that is unable to meet even that basic standard. This is a system in crisis and prone to crisis. It is important, however, to recognise that this crisis is a crisis for renters. For landlords, this is the dream. In this crisis, they hold all of the power. As such, there is no ‘one weird trick’ that will enable housing to act as an investment asset solely geared towards the continual growth of wealth for private actors, while guaranteeing adequate and affordable housing for all.

Intervention is needed. This intervention requires both reforming and rebalancing the rental system to better protect the rights of tenants and to stabilise rental increases, as well as significant and sustained investment to increase the stock of public and community housing.

Increasing the supply of housing to keep pace with population growth is clearly required. But increasing supply cannot happen overnight and it is not a panacea for all of the problems in the rental market. It has been observed that growth in the mid-to-high price segments of Australian housing supply does not necessarily create a ‘trickle-down’ effect into the low-price segments by freeing up established housing stock.[3] This lack of trickle-down was reflected in the findings of the WA Housing Industry Forecasting Group, which noted that even during the period of 2017-18 where there were historically high levels of rental stock in Western Australia, ‘for those on the lowest incomes, conditions have not changed.’[4]

Western Australian community services report that they are now seeing large numbers of clients who are in private rental arrears. Demand for emergency relief funds to cover these arrears is growing, with many people seeking support having experienced substantial rent increases. One service reported to WACOSS that a client had their rent increase by $200 per week.

The inability of the market to ensure the supply of affordable housing for low-income and at-risk households is why ambitious State and Federal Government investment in public and community housing is so necessary. Direct public investment is the single most cost-effective way to scale up social housing stock, boosting employment opportunities and income.[5]

Rents are on the Rise

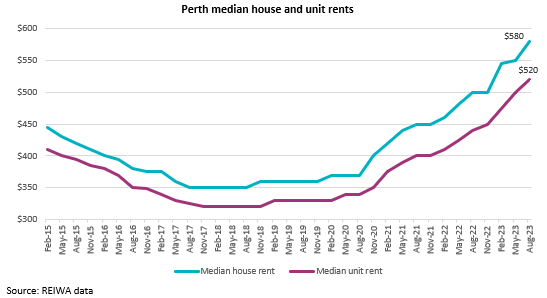

Housing is the single largest living cost for households in Western Australia, and housing costs have a disproportionate impact on those living on the lowest incomes.[6] With median rents in Perth on the increase since 2018, and drastically rising since 2020, the pressure on households due to rental costs has never been more apparent.

As of August 2023, median house rents in Perth had increased by more than 16 per cent over the past 12 months and by 28.9 per cent since August 2021. Median unit rents also saw significant increases of 18.2 per cent since 2022 and by 30 per cent since 2021.[7]

Perth median house and unit rents

Source: REIWA data

The increasing lack of affordable rental properties in Western Australia is reflected in the latest Rental Affordability Index results. Perth’s rental affordability index score declined to its lowest level since 2016, with a drop of 15 per cent over the past two years. Over the past year, regional WA saw a decline of 8 per cent in its rental affordability index score. Rent as a share of income for a single person on JobSeeker was calculated to be 111 per cent in Greater Perth and 110 per cent in the rest of Western Australia.[8]

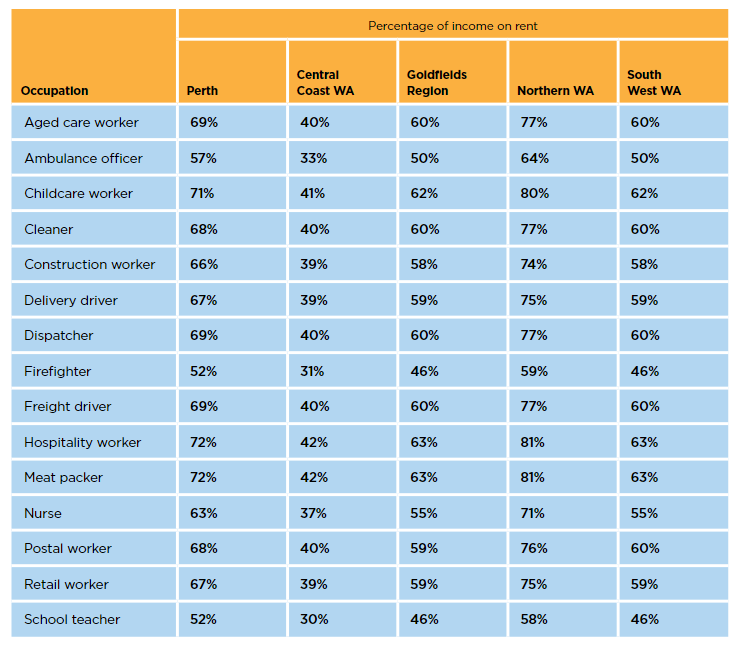

Housing costs have a disproportionate impact on those living on the lowest incomes.[9] A recent report by Anglicare Australia and Everybody’s Home, a national coalition of housing, homelessness and welfare organisations, has revealed the impact high rents are having on essential workers. This analysis compares data on rents against the award wages for fifteen essential worker categories.

In this report, workers in hospitality, meat packing, child care and aged care were found to be spending the highest percentage of their income on rent. In Perth, all of the fifteen essential worker categories were found to have to spend in excess of 50 per cent of their income on rent, with hospitality workers and meat packers having to spend 72 per cent of their income. In Northern Western Australia, hospitality workers and meat packers would have to spend over 80 percent of their income on rent.[10]

Income on Rent, Western Australia (%)

Source: Anglicare Australia and Everybody’s Home (2023)

A recent survey of 330 renters published in April 2023 by Make Renting Fair WA found that 58 per cent of respondents had experienced at least one rent increase in the last two years, and 14 per cent having experienced two rental increases. 33 per cent of survey respondents had a rent increase between $21 and $50 per week, 10 per cent had a rent increase between $51 and $75 per week, and 11 per cent had a rent increase between $76 and $100 per week. 57 per cent of respondents reported that they had found these increases difficult. 80 per cent of respondents reported that if their rent was to increase by a further 10 per cent over the next 12 months, that they would find such an increase difficult.[11]

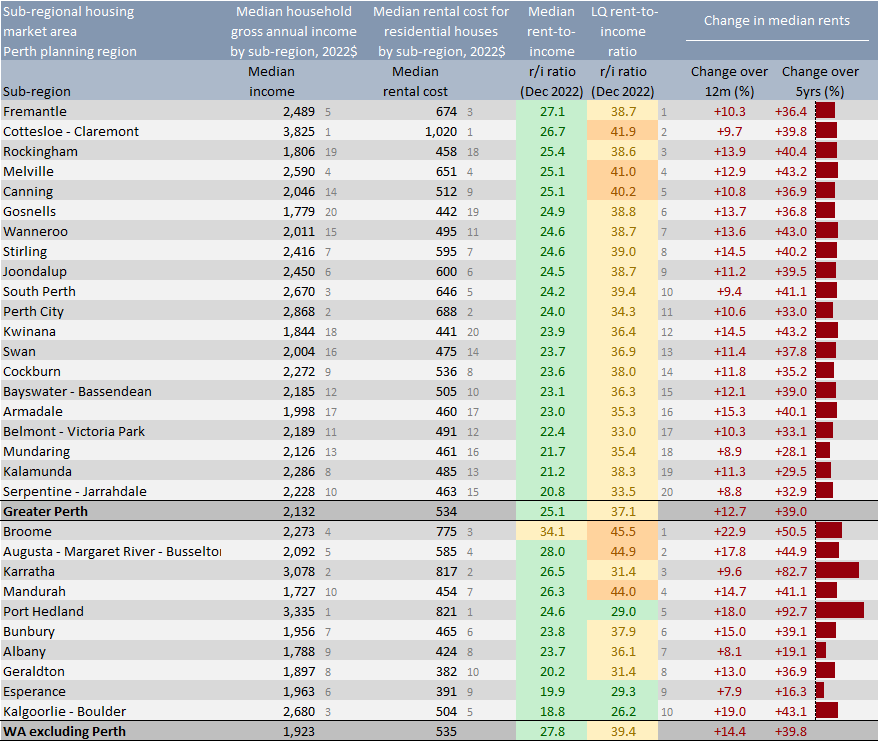

Recent analysis by the Bankwest Curtin Economic Centre found that the cost of lower quartile rental properties has risen even faster than the rest of the market. No sub regions in Greater Perth were deemed to be affordable for lower income households, with rental costs comprising between 33 per cent and 42 per cent of income in every metropolitan area. Regional housing markets have also observed substantial and unaffordable rental increases, with the lower quartile rent to income ratio for Broome at 45.5 per cent, Port Hedland at 44 per cent, and the Augusta – Margaret River – Busselton nexus at 44.9 per cent.

Notably too, the report found that recent percentage rises in rental costs have been as high or higher in suburbs that have been traditionally considered more affordable. Over the past 12 months, some of the highest proportional increases in rental costs were observed in Kwinana at 14.5 per cent, Gosnells at 13.7 per cent and Armadale at 15.3 per cent. [12]

Rental costs for established houses by Perth suburb and WA region: 2022

Source: Bankwest Curtin Economics Centre (2023) Housing Affordability in Western Australia.

The findings of these reports and the Make Renting Fair survey make clear how unaffordable the rental market has become for people on low incomes in WA. The more of their income that households must dedicate to covering housing costs, the less they will be able to spend on other essentials like food, energy and health. It can also mean that any slight increase in their rent can have a dramatic impact on their ability to stay in a property and maintain the important connections they have established throughout their local community, along with their proximity to jobs and services.

Case Studies

The following real-life case examples have been provided to WACOSS by the Financial Wellbeing Collective. The names of the clients have been changed to protect their privacy.

James called seeking assistance with food. James works full time; his partner is a stay-at-home mum to their 2 young children. James advised their hardship is caused by a recent rent increase of $75 per week, they were already struggling to pay the rent previously and the most recent increase of $75 has really impacted on their ability to afford the basics such as food. They also had to add an extra $300 to their bond which was extremely difficult for the family.

Martha is 81 years old with no family or friends and is struggling to make ends meet. Her landlord will only give her 6-month leases since the rent prices have increased and every time her lease is renewed, the rent is also increased by $50pw. This is putting a lot of financial stress on Martha.

Sarah had to vacate her rental due to the landlord putting the property on the market, and after searching for months, the only place they could find cost $300 more per week in rent. Sarah has 2 adult children forced to live in the house and unable to contribute financially. Sarah receives Centrelink for one dependent child.

Donald called seeking assistance with multiple bills. Donald advised he only works casually and his partner works part time. Their rent has been increased by $100 per week. They were already struggling to pay their rent, but this has further impacted them. They also need to produce a $400 bond top up payment.

Sandra is on a disability pension receiving $607.50 per week, with her rent increasing constantly. It is currently $475 each week which only leaves Sandra with $132.50 to live on and pay her bills. She is falling behind with all her utility bills as well as her rent. She is finding it extremely difficult to put food on the table, which is causing her stress and affecting her mental health.

Hannah called in requesting food assistance as her rent has been increased by $160 per week. She must now also produce a bond top up of $640. Hannah is a single parent to one child, working part time earning $400 per week and receiving family tax benefit. Hannah was already struggling with rising costs and this increase will make it even more difficult for her to make ends meet.

Reforming the Rental Market

With rental vacancy rates at such historic lows and many WA households struggling to find affordable places to rent, we cannot afford to have residential properties sitting empty. A vacant residential property charge can ensure the most efficient use of housing stock by discouraging investors and developers from leaving dwellings empty. This is particularly important during the current period, where supply is struggling to keep up with the demand for rental housing, leading to exorbitant rent increases.

The WA Government acted swiftly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic by introducing the Residential Rent Relief Grant Scheme to assist tenants experiencing financial hardship. With rents continuing to skyrocket in this overheated rental market, we consider that there is a clear need for the scheme to be reintroduced to provide support for tenants until such time as the market cools.

Such a scheme should be accompanied by the introduction of strict limits on rent prices and increases. The knee-jerk opposition that emerges from certain quarters to the spectre of ‘rent control’ does not engage seriously with the international evidence and developments in that policy area. Instead it is driven by self-interest and a rejection of the critical role of the state in the regulation of markets.[13] Further, there is a tendency to oppose all forms of rent control as though what is being proposed are the hard ‘first generation’ rent freezes of which there are few examples past the 1960s,[14] aside from forming part of necessary emergency responses to crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

In contrast, the Global Research Head of Aberdeen Standard Investments wrote in the Financial Times that the German experience has demonstrated to them that rent control has benefits for both landlords and tenants due to the stability and predictability that it creates.[15] Similarly, research conducted for the Residential Landlords Association by the London School of Economics, found that rent stabilisation and indexation have been a core element in building sustainable private rental markets in places like Europe.[16]

It is exceptionally challenging for tenants in the Australian rental markets to challenge increases in rent. This is both because tenants fear that landlords will mark their attempts to do so against them, potentially leading to their eviction, and due to the asymmetry of information, with market data far more readily accessible for landlords and property managers than tenants.

WACOSS proposes the introduction of second-generation rent stabilisation measures that place a cap on rents that limit increases to no more than the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The landlord should also be prevented from increasing the rent between the end of one tenancy and the start of another by more than CPI. This is necessary to avoid incentivising landlords to terminate tenancies in order to charge higher rents.

We recognise that there may be limited circumstances where it is reasonable for the rents to increase by more than CPI, such as when substantial improvements have been made to the property. In those circumstances, however, any proposed increase above CPI should have to be justified by the landlord to the State Administrative Tribunal.

Improving Renters’ Rights

The landlord/tenant relationship is an inherently inequitable one. In Western Australia, this inequity is compounded by the disempowerment of renters under current legislation. The limited protections and rights granted to renters are substantially undermined by the priority accorded to the interests of landlords. In May 2023, the Western Australian State Government announced that it would modernise the Residential Tenancies Act 1987. The proposed changes include:

- prohibiting the practice of rent bidding, with landlords and property managers unable to pressure or encourage tenants to offer more than the advertised rent;

- reducing the frequency of rent increases to once every 12 months;

- tenants will be allowed to keep a pet or pets in a rental premises in most cases;

- tenants will be able to make certain minor modifications to the rental premises and the landlord will only be able to refuse consent on certain grounds;

- the release of security bonds at the end of a tenancy will be streamlined, allowing tenants and landlords to apply separately regarding how bond payments are to be disbursed; and

- disputes over bond payments, as well as disagreements about pets and minor modifications, will be referred to the Commissioner for Consumer Protection for determination.[17]

Though all of these proposed changes are needed, they are insufficient to meaningfully rebalance the landlord/tenant relationship. That requires the abolition of ‘no-grounds’ or ‘without grounds’ evictions. It is also essential that mandatory minimum energy efficiency standards for rental properties are introduced to ensure tenants are able to access liveable, quality housing options.

No-Grounds Evictions

Abolishing ‘no-grounds’ terminations is fundamental to creating a more equitable rental framework. While it remains the case that a tenant can be evicted without a demonstrable cause, the ability of tenants to exercise their rights is significantly diminished. As a result, this is one of the key reforms that needs to occur in order to support all other rights of renters

Renters deserve assurance that if they have not breached the terms of their lease agreement, their tenancy will not be terminated. The current provision unjustly places renters in a deeply precarious position, establishing a systemic power imbalance between tenant and landlord. This power imbalance acts as a substantial deterrent for renters to make any requests of the property manager or landlord, or take any action which may inadvertently put their tenancy at risk. As a result, they are less willing to make requests or take actions that may increase their health, safety or comfort.

No-grounds’ terminations should be replaced with a list of prescribed reasonable grounds for eviction, which would provide landlords with adequate rights and protections. It is crucial that this list is exhaustive and not too broad in scope, in order to also provide adequate protections for renters. The legislation must recognise that a tenant’s basic right to shelter and security takes precedence over a landlord’s discretion to terminate a lease.

The ability to terminate a tenancy without grounds should not only be abolished in relation to periodic tenancies, but also through the use of ‘end of fixed term’ notices. Allowing the termination of tenancies simply through the issuing of an ‘end of fixed’ term notice when the end date arrives, should be recognised as another form of without grounds terminations that likewise results in significant housing insecurity for renters. Further, without their removal, short fixed-term tenancies will be utilised by landlords to circumvent any other reform that restrict their ability to terminate leases without cause.

Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards

Inadequate housing costs us all more as a community, through the associated burden of chronic disease. Households living in poor quality housing have limited capacity to reduce their exposure to extreme heat, and older households often underestimate their vulnerability to adverse health outcomes. Many aged pensioners put their health and life at risk in an effort to keep energy bills down, leading to poorer wellbeing outcomes and rising health care costs.

Empowering renters to make better choices about the properties they rent can be achieved through the mandatory disclosure of relevant information. In a tight rental market such as we have currently, however, where renters may have limited options to choose from, improved information will not be sufficient to achieve tangible outcomes. As such, minimum standards need to be established to ensure tenants are able to access liveable, quality housing options, as are being progressively introduced in Victoria, Queensland and the ACT.

The lack of minimum standards in rental properties places the health and wellbeing of renters at risk. The fear of eviction can deter tenants from seeking repairs to the rental property from real estate agents and landlords. Due to the very low supply of genuinely affordable rental properties for those on the lowest incomes, as well as discrimination in the rental market, low income renters may be forced to compromise on housing quality. Minimum standards that must be met for all rental properties establish a clear baseline that can be easily understood by landlords and tenants. These minimum energy efficiency standards should also support the electrification of rental properties.

Landlords are in the business of providing a product for profit. As such, we should be able to expect that product to meet a certain standard, and considering these are places in which people spend a considerable proportion of their lives, it is not unreasonable that we expect those standards to be high.

Public Housing

Discriminatory provisions in residential tenancy legislation need to be removed to ensure that public housing tenants are entitled to the same rights and protections as renters in the private market.

As identified by the WA Equal Opportunity Commission, public housing tenants in many cases are ‘subject to a harsher regime than tenants in the private market.’[18] The Commission notes the ways in which this is enabled by the RTA, with the use of section 75A in particular applying ‘a stricter standard to public housing tenants than non-public housing tenants.’ The Commission notes that under section 75A of the Western Australian Residential Tenancies Act, public housing tenants can be subject to eviction due to so-called ‘disruptive behaviour’. This behaviour could be minor, such as excessive noise, and would not result in eviction for private housing tenants engaged in the same actions.

With public housing tenants at significant risk of homelessness should they be evicted, it is manifestly unjust to subject them to such a punitive approach. Public housing tenants deserve the same level of basic rights and protections as any other renter, if not more as they may be navigating the system while dealing with the impacts of poverty, illness, trauma and other challenges.

WACOSS also calls for all governments to adopt a target of zero children evicted to homelessness from public housing, with public reporting requirements on meeting this target. This should be accompanied by the necessary legislative reform to ensure that appropriate support programs are in place to prevent evictions from occurring.

For enquiries on this submission, please contact:

Graham Hansen, Senior Policy Officer, [email protected], 08 6381 5300.

References

[1] National Association of Tenant Organisations, National Shelter, Everybody’s Home and Better Renting, ‘Tenant advocates to National Cabinet: no time for half-measures on renters’ rights‘, Tenants Union of New South Wales (Web Page, 02 May 2023).

[2] Grundgesetz für die Bundesrepublik Deutschland [Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany] art 14.

[3] Rachel Ong et al, Housing supply responsiveness in Australia: distribution, drivers and institutional settings (Final Report No 281, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, 2017).

[4] Housing Industry Forecasting Group, Forecasting Dwelling Commencements in Western Australia 2017-2018 (Report, 2017).

[5] Julie Lawson et al, Social housing as infrastructure: an investment pathway (Final Report No 306, Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute, 2018).

[6] ACOSS/UNSW Poverty and Inequality Partnership, Poverty, Property and Place: A geographic analysis of poverty after housing costs in Australia, (Report, City Futures Research Centre & the Social Policy Research Centre, 2020).

[7] REIWA, Perth market insights (Web Page, 2023).

[8] National Shelter, the Brotherhood of St Laurence, and SGS Economics and Planning, Rental Affordability Index (Report, 2022).

[9] ACOSS/UNSW (n 6).

[10] Anglicare Australia and Everybody’s Home, Priced Out: An Index of Affordable Rentals for Australia’s Essential Workers (Report, 2023).

[11] ‘New survey data shows full impact of unlimited rent increases’, Make Renting Fair WA (Web Page, 2023)

[12] Ryan Brierty et al, Housing Affordability in Western Australia 2023: Building for the future (Bankwest Curtin Economic Centre Focus on WA Report Series, No 17, May 2023).

[13] Tom Slater, ‘From displacements to rent control and housing justice’ (2021) 42(5) Urban Geography 701, 702.

[14] Christine Whitehead and Peter Williams, Assessing the evidence on Rent Control from an International Perspective (Report, October 2018) 10.

[15] Andrew Allen, ‘German rent control works for both landlords and tenants’, Financial Times (online, 13 March 2019).

[16] Whitehead (n 14).

[17] ‘WA tenancy law modernization to strike a balance between tenants and landlords’, Department of Mines, Industry, Regulation and Safety (Web Page, 26 May 2023).

[18] Equal Opportunity Commission, A Better Way: A report into the Department of Housing’s disruptive behaviour strategy (Report, 2013).